The True History of Mulakkaram

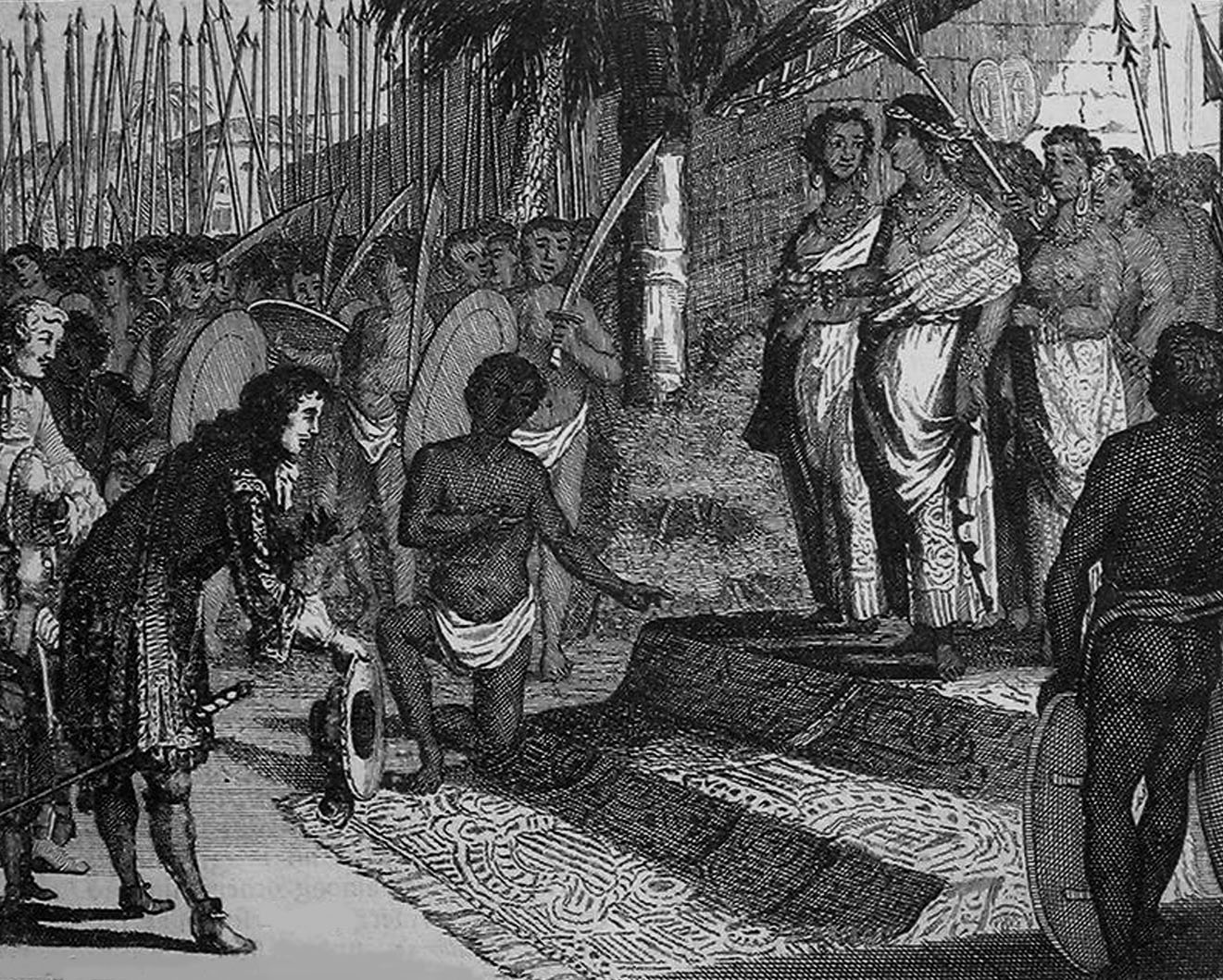

Artistic depiction of the story of Nangeli, an Ezhava woman to have lived in the early 19th century in Cherthala in the erstwhile princely state of Travancore in India, and supposedly cut off her breasts in an effort to protest against a tax on breast.

A commonly cited misconception associated with caste-based discrimination in Kerala is the so-called “Breast Tax” Central to this narrative is the legend of Nangeli, described as a lower-caste woman from nineteenth-century Travancore (present-day Kerala) who allegedly protested the imposition of this tax by severing her breasts and presenting them to a tax collector, an act that purportedly resulted in her death from blood loss. This story was even repeated by the ex-CJI DY Chandrachud. Although this story has gained prominence as a symbol of resistance against caste and gender oppression, several historians argue that the story lacks contemporaneous documentation and is rooted primarily in later folklore. Notably, early records do not even identify Nangeli by name, raising serious questions regarding the historical authenticity of the narrative.

The term “Breast Tax” commonly referred to as Mulakkaram, is used to describe a historical practice in the princely state of Travancore that is often interpreted as reflecting the intersection of caste and gender hierarchies. This tax is frequently portrayed as being imposed on women from lower-caste communities such as the Nadar and Ezhava, and is cited as an instrument of social subjugation during the nineteenth century. However, while certain taxation practices undoubtedly reinforced social stratification, the precise nature, scope, and intent of Mulakkaram remain subjects of scholarly debate. The lack of clear legal documentation suggests that some modern interpretations may rely more on retrospective moral frameworks than on verifiable historical evidence.

Historically, numerous taxation systems that appear unjust or irrational by contemporary standards were normalized within their original socio-cultural contexts. These fiscal measures reflected the economic priorities, political structures, and social norms of their respective periods. Over time, as ethical standards and societal values evolved, many such taxes were rendered obsolete or indefensible. For example, eighteenth-century England imposed a tax on wig powder, a commodity associated with aristocratic status and luxury. Given the material similarity between wig powder and other aromatic powders, this tax effectively extended to a wide range of cosmetic products. Comparable levies included the window tax, calculated based on the number of windows in a building; the candle tax, imposed on wax candle usage; and the soap tax, which targeted a basic household necessity. Although these measures generated revenue, they disproportionately affected certain social classes and were eventually abolished due to growing public opposition.

A similar pattern can be observed in the case of the Chinese Head Tax in Canada, enforced until 1923. This racially discriminatory policy targeted immigrants of Chinese origin and was explicitly designed to restrict Chinese migration while extracting economic benefit from an already marginalized community. Rooted in the xenophobic attitudes of the time, such a tax would be considered a blatant violation of equality and human rights if proposed in contemporary society. Its eventual repudiation illustrates the transformation of societal norms regarding race, justice, and citizenship.

These examples demonstrate how taxation policies, once consistent with prevailing ideologies, can later be recognized as manifestations of structural injustice. They underscore the necessity for fiscal systems to evolve in accordance with ethical progress and social equity. In this broader context, Kerala too witnessed several forms of taxation that appear unusual by modern standards but were widely accepted at the time of their implementation.

These included taxes such as Mulakkaram (breast tax), Meesakkaram (moustache tax), ladder tax, death tax, and taxes on roofing materials. Importantly, many of these were not formal statutory taxes enacted through royal decrees or codified laws. Instead, they often emerged from customary practices that gradually acquired the character of obligatory payments. Both men and women engaged in agricultural and domestic labor were required to pay various fees for rights related to land cultivation (Verumpattam) and residence (Koodiyedappu). Gender distinctions in these payments were symbolically indicated through references to physical markers such as breasts for women and moustaches for men, rather than constituting literal taxes on the body.

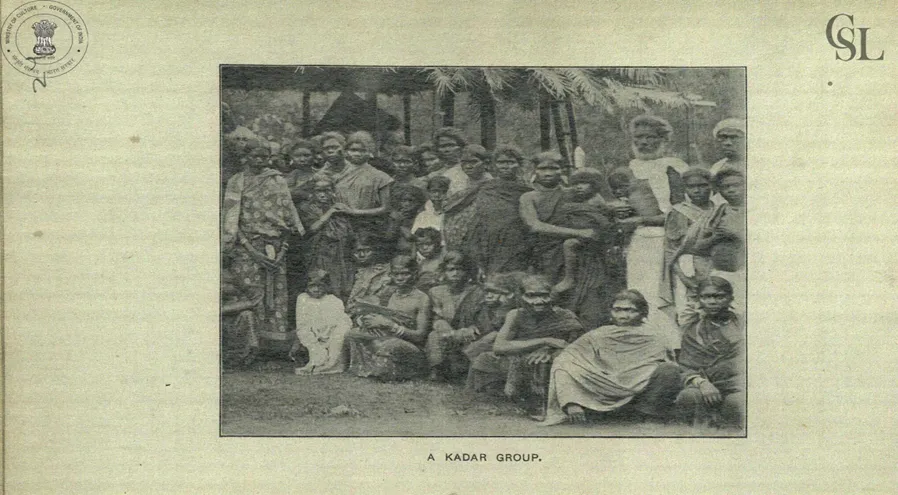

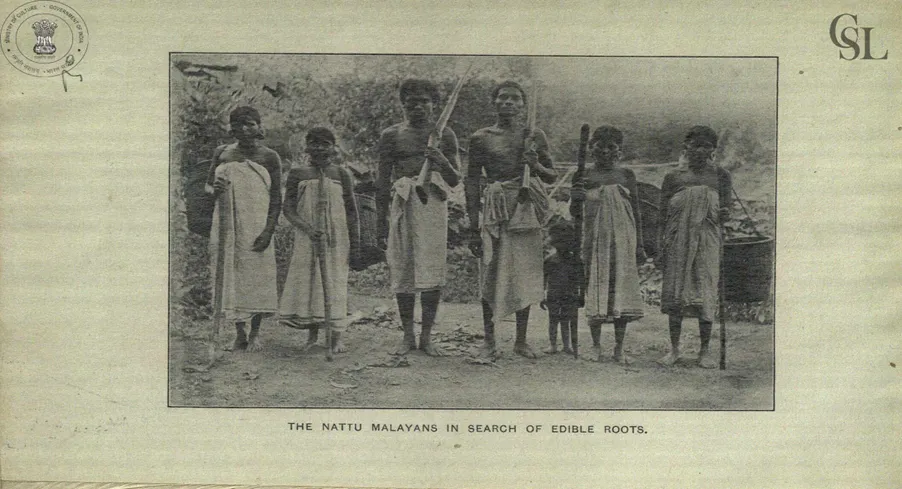

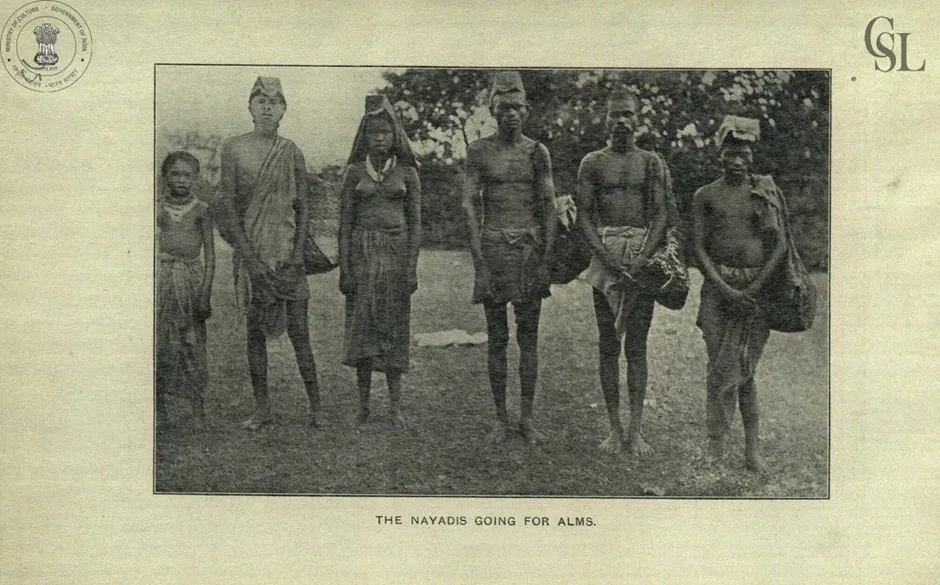

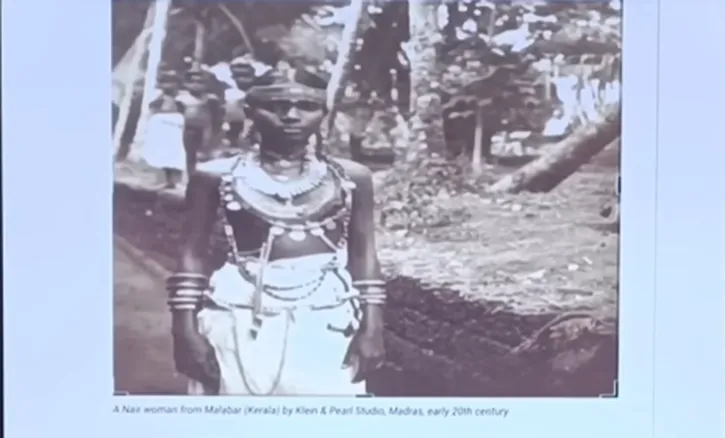

A persistent contemporary myth claims that lower-caste communities were systematically forced into nudity by upper castes through prohibitions on upper garments and punitive taxation. Historical evidence, however, complicates this assertion. Ethnographic works such as The Cochin Tribes and Castes (1909) document visual representations of both upper- and lower-caste women who appeared unclothed above the waist. These depictions suggest that upper-body nudity was influenced by regional customs, climatic conditions, and social norms rather than being solely the result of caste-based coercion.

This is an image of a tribe community called “Kadar,” where the women are covering the top part of their bodies.[1]

An image of a tribe community called “Nattu Malayan,” the women are covering the top part of their bodies.[2].

An image of a tribal community called “Nayadis” shows that the women are not covering the top part of their bodies.[3]

An image of a girl from the community called “Nair/Nayar,” the woman is not covering the top part of their body.[4]

Another image of a girl from the “Nair/Nayar”, community the woman is not covering the top part of their body.[5]

The traveler Johannes Nieuhof records in his work Voyages and Travels into Brazil and the East-Indies that:

“The 2nd of March with break of day,

The author goes to the queen of Koulang.The viceroy of the king of Travancore, called by them Gorepe, the chief commander of the Negroes, called Mattia del Pule, and myself, set out for the court of the queen of Koulang, which was then kept at Calliere. We arrived there about two o’clock in the afternoon, and as soon as notice was given of our arrival, we were sent for to court, where, after I had delivered the presents, and laid the money down for pepper, I was introduced into her majesty’s presence. She had a guard of above 700 soldiers about her, all clad after the Malabar fashion, the queen’s attire being no more than a piece of calico wrapped round her middle, the upper part of her body appearing for the most part naked, with a piece of calico hanging carelessly round her shoulders. Her ears, which were very long, her neck and arms were adorned with precious stones, gold rings and bracelets, and her head, covered with a piece of white calico. She was past her middle age, of a brown complexion, with black hair tied in a knot behind, but of a majestic mein, she being a princess who showed a great deal of good conduct in the management of her affairs. After I had paid the usual compliments, I showed her the proposition I was to make her in writing, which she ordered to be read twice, the better to understand the meaning of it, which being done, she asked, whether this treaty comprehended all the rest? and whether they were annulled by it? Unto which I having given her a sufficient answer, she agreed to all our propositions, which were accordingly signed immediately.”[6]

Several cinematic representations have portrayed the narrative of Nangeli and the so-called Breast Tax through a lens of heightened emotional appeal. These portrayals often rely on dramatization rather than verifiable historical evidence, thereby reinforcing a contested and largely unsubstantiated account. Such representations risk shaping public perception through selective storytelling rather than critical historical inquiry.

Several cinematic representations have portrayed the narrative of Nangeli and the so-called Breast Tax through a lens of heightened emotional appeal. These portrayals often rely on dramatization rather than verifiable historical evidence, thereby reinforcing a contested and largely unsubstantiated account. Such representations risk shaping public perception through selective storytelling rather than critical historical inquiry.

In parallel, this narrative has been appropriated by certain evangelical groups, who have employed it as part of broader conversion-oriented discourses aimed at marginalized communities, including sections of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe populations. Scholars have noted that the use of emotionally charged historical narratives in this manner can obscure historical complexities and instrumentalize suffering for ideological purposes.

Additionally, some commentators have attributed the abolition of the alleged Breast Tax to Tipu Sultan, despite the absence of credible historical evidence supporting such claims. These assertions often conflate distinct historical contexts and timelines, resulting in anachronistic interpretations. Furthermore, references to the Breast Tax have, in certain cases, been invoked to rationalize or contextualize episodes of communal violence, including the persecution of Mandyam Iyengar communities.[7] The use of disputed historical narratives to justify or explain acts of violence raises serious ethical and historiographical concerns, underscoring the importance of rigorous, source-based analysis.

Citations

[1] The Cochin Tribes and Castes, Vol 1, p.25.

[2] Ibid., p.35.

[3] Ibid., p.52.

[4] A Nair woman from Malabar (Kerala) by Klein & Peail Studio, Madras, early 20th century.

[5] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Breast_exposed_Nayar_Girl.jpg

[6] Johannes Nieuhof, Voyages and Travels into Brasil and the East-Indies, p.218-19.

[7] Vikram Sampath, Tipu Sultan: The Saga of Mysore’s Interregnum (1760–1799),pp.288–289.