The British, The Congress, and The RSS

Time and again, Congress leaders spew baseless rhetoric about the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Recently, Priyank Kharge, a “Dalit” leader, three-time MLA from Chittapur, and full-time RSS-obsessed heckler and a part-time politician, never misses a chance to take cheap shots. In a recent ‘X’ post, he tried to mock the RSS with a series of hollow questions, including the tired claim that the RSS never took part in the freedom struggle.

Naturally, he didn’t bother to provide a shred of evidence. Expecting factual references from Congress’s noise-makers is like expecting logic from chaos; it’s simply not going to happen. Just like that, we repeatedly see Congress members shamelessly peddling absurd and historically illiterate comparisons between the RSS and the Nazis. This is not just a lazy slur; it is a deliberate distortion rooted in a calculated political history that deserves to be exposed. Let's start with the founder of RSS himself. Dr. Hedgewar. In 1905, as the flames of the Swadeshi movement swept across India, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Antaji Damodar Kale founded the ‘Paisa Fund Society’ to strengthen the nationalist cause. A young, fiercely patriotic K. B. Hedgewar threw himself into the effort, going door-to-door to collect funds for the mission. Not stopping there, he joined the Arya Bandhav Veethika, an organisation formed by Nagpur’s revolutionaries to spread the spirit of Swadeshi, and began visiting schools, igniting in students the resolve to reject foreign goods and embrace indigenous pride.[1]

At just sixteen, Hedgewar rallied together a circle of sharp, restless students, forging a discussion group that debated the issues of the day. His growing nationalist fire soon drew him into the covert network of the Deshbandhu Samaj, an underground collective quietly shaping the revolutionary undercurrent of the era.[2] Hedgewar’s patriotism went further in September 1907, when he and several fellow students defiantly raised the slogan Vande Mataram during a school inspector’s visit. Ordered to apologize, Hedgewar refused outright, choosing principle over punishment. His unyielding stance led to his expulsion, and it was widely believed that he was the chief force behind the students' coordinated act of resistance.[3]

According to his childhood friend Balwant Mandelkar, Hedgewar, along with a small circle of determined students in Nagpur, had secretly learned bomb-making techniques in a clandestine workshop reportedly organized by B. S. Moonje between 1905 and 1906.[4] The following year, in August, Hedgewar threw a homemade bomb at a local police station. The attempt failed to hit its mark, and with no evidence left behind, he slipped through the grasp of colonial authorities. Yet his revolutionary spirit didn’t go unnoticed for long. He was soon arrested for delivering a fiery political speech demanding an end to British rule before a massive crowd gathered for the Dussehra burning of Ravana’s effigy. Thanks to the intervention of influential local leaders, he was released, and the charges were withdrawn. These events pushed Hedgewar deeper into nationalist circles.

N.H. Palkar, the author of ‘Man of the Millennia-Dr. Hedgewar’ notes that it was Guha who first ushered Hedgewar into the inner circle of the Anushilan Samiti, giving him access to one of Bengal’s most influential revolutionary networks.[5] Hedgewar is also believed to have formed a close association with Shyam Sundar Chakravarti, a hardened nationalist and vocal critic of Chittaranjan Das. Some accounts further claim that he maintained contact with towering figures such as Motilal Ghose, Rash Behari Bose, Ashutosh Mukherjee, and Bipin Chandra Pal. However, these assertions remain unproven and lack documentary evidence.[6]

Ramlal Bajpayee, a lawyer residing in Calcutta during this period, records in his autobiography that Hedgewar’s true purpose in going to Calcutta was far deeper than formal studies; he sought to master the workings of clandestine revolutionary societies and forge a living bridge between the nationalist movements of Maharashtra and Bengal. Driven by this mission, Hedgewar shuttled between Nagpur and Calcutta repeatedly from 1910 to 1913, cultivating networks, absorbing underground methods, and weaving together the revolutionary currents of both regions.[7]

Anushilan Samiti flag

Bhupati Majumdar, a young Anushilan Samiti member who would later serve as a minister in the West Bengal government, recalled in his memoirs the encounters he had with Hedgewar during those turbulent years. Majumdar states that Hedgewar, acting as the key liaison for Maharashtrian revolutionaries operating in Bengal, maintained direct contact with Jatindranath Mukherjee, the legendary ‘Bagha Jatin.’ He further claims that Hedgewar actively supported Jatin’s covert efforts to procure arms and ammunition from abroad, a daring enterprise that would later be known as the Hindu–German conspiracy.[8]

Whatever the precise extent of Hedgewar’s involvement with Bengal’s revolutionary networks, one fact was undeniable: the Calcutta police had already marked him as an ‘extremist student’. His movements did not go unnoticed. By early 1912, he had drawn the attention of the Director of Criminal Intelligence, and colonial surveillance tightened around him, reflecting the growing unease British authorities felt toward young nationalists who refused to stay within their control. Calcutta, reported:

On January 31st, Narayan Damodar Savarkar arrived at the Maratha Lodge in Prem Chand Boral's Street and took up his residence there. It is said that Dr. S.K. Mullik is not prepared to admit him as a student of the National Medical College. Soon after his arrival Savarkar was introduced to Hidgewar (sic), Ane, and Naik, three well-known extremist students of the Santi Niketan Maratha Lodge.

On February 3rd, D.V. Vidhwans, the son-in-law of B.G. Tilak, arrived at the Maratha Lodge in Prem Chand Boral's Street from Poona on his way to see Tilak in Mandalay. On his arrival the student Hidgewar mentioned above went and fetched Babu Shyam Sundar Chakravarti (one of the deportees) to the Lodge, and all three had a long conversation. Shyam Sundar Chakravarti is again coming to the front as an extremist.[9]

Hedgewar travelled tirelessly across the Hindi-speaking regions of central India, widening the reach of the weekly and, in the process, forging relationships that would later prove indispensable when he founded the Sangh.[10] His growing disillusionment with the Congress’s definition of Swaraj, as nothing more than self-government within the British Empire, pushed him to chart his own path. He established the Nagpur National Union, an organisation committed to the goal of complete independence.[11]

Portrait of Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (1 April 1889 – 21 June 1940)

Yet this ideological divergence did not prevent him from plunging deeper into the Congress’s organisational activities. These experiences only sharpened his belief in the necessity of a permanent, disciplined cadre. Observing how, in his words, ‘Congressmen are good orators who impress people in the first meeting, but their impact fades from public memory within two or three days,’[12] Hedgewar became ever more convinced that India needed a force rooted in long-term organisation rather than fleeting rhetoric. Hedgewar went ahead and joined the non-cooperation movement in 1920 and addressed several meetings in the party as well as in Bombay.[13]

In 1922, Hedgewar, with the support of Ganga Prasad Pande, set up a National Wrestling School, an institution meant to instill discipline, strength, and nationalist spirit in young men. But the venture soon drew the unwelcome gaze of the Punjab Police and the CID in Nagpur. Their persistent interference and surveillance ultimately forced the school to shut down, yet another reminder of how colonial authorities sought to crush even the smallest sparks of organised national awakening.[14]

To spread the ideals of the Congress and boldly champion the demand for complete independence, Hedgewar, along with a few prominent Congress colleagues, launched a new Marathi daily, Swatantrya, in January 1924. His unwavering sympathy for revolutionary nationalism reverberated through his speeches, writings, and the paper’s editorial line. But his radical stance soon alarmed the more cautious sections of society. Advertisers began to withdraw, and the revenue stream steadily collapsed. Within a year, by January 1925, Swatantrya became financially unsustainable and was forced to shut down.[15]

In 1930, the entire nation was ablaze with the Civil Disobedience Movement. In July, Hedgewar travelled to the small town of Pusad in Yavatmal district to join the satyagraha, temporarily handing over the responsibilities of sarsanghchalak to Dr. L. B. Paranjpe. While in Pusad, he intervened to prevent the slaughter of a cow near the riverbed, an act that sent shockwaves through the town. After addressing a protest gathering there, he moved on to Yavatmal to participate in another act of civil resistance: cutting grass in a government-reserved pasture. Hedgewar was arrested on 21 July along with his fellow satyagrahis and sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.[16] They were housed in makeshift warehouse barracks near the Akola prison, nearly 250 kilometres from Nagpur. As the harsh conditions took a toll on his health, the prison superintendent intervened, and Hedgewar was released on 14 February 1931. It had been over five years since Hedgewar had founded the RSS, and its roots were already spreading. Even during his stay in Pusad, he established a shakha (branch), planting yet another seed of the growing movement.[17] After his release from prison, Hedgewar emerged with renewed resolve. He set out to elevate the RSS from a regional initiative to a truly national organisation, one capable of shaping disciplined, dedicated workers across the length and breadth of the country.

The government of the Central Provinces and Berar had begun watching the RSS with growing unease, scrutinising its every move and debating what punitive measures might be imposed. After the Dussehra celebrations of 1932, official reports voiced explicit concern over Hedgewar’s expanding influence and uncompromising views, signalling that the colonial administration now considered the RSS a force worth monitoring, if not suppressing:

“In the south of the province the most important political feature has been the celebration at Nagpur by the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh of the Dasehra festival, of which advantage is taken each year to hold a ceremonial worship of arms and a review of volunteers. On the present occasion 1,000 uniformed volunteers, under the leadership of Dr. Munje (sic), headed by a band and accompanied by their ambulances, marched past an assemblage which included the Bhonsla Raja G.D. Savarkar, Dr Hidgewar (sic), and others. The drill is reported to have been good. The chief speakers at these celebrations were Dr Munje (sic), and Dr Hidgewar (sic), the second of whom gave an objectionable and provocative address, the main gist of which was that the settlement of the political future of India was for the Hindus alone to decide. No interference either by foreigners or by non-Hindu residents of India should be brooked. The question whether action should be taken against the speaker is under Government's consideration”.[18]

By this time, the government’s continuous surveillance had given it a clearer, though deeply distorted, view of the RSS. Certain sections of the colonial administration began drawing reckless parallels between the organisation and European extremist movements, going so far as to label Hedgewar as a ‘Hitler,’ a comparison rooted more in British fear than fact.

In February 1935, the Criminal Investigation Department’s Special Branch in Allahabad submitted a report to the Chief Secretary of the United Provinces, noting the rapid rise of the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh, described as a volunteer corps parallel to the Congress’ Hindustani Seva Dal. The report detailed the Sangh’s growing network across the Central Provinces, Berar, and the United Provinces, along with its ambition to establish branches throughout the country. It further observed that the Sangh’s presence in the United Provinces was, at that point, concentrated mainly in Benares and strongly centered around disciplined, military-style drills:

The object of this organization is to infuse a military spirit in the Hindus, to impart physical training and to educate them in the use of lathis, spears and daggers and (as was publicly announced at a meeting in Nagpur in 1932) to build up an All-India Hindu Volunteer Corps on the same lines as those of the Nazis under Hitler in Germany. Dr. Hidgewar (sic) (C. P. Who's Who no. 114) is the Hitler of the Sangh.

The All-India Mahasabha held at Delhi in September 1932 passed a resolution admiring the efforts of Dr. Hidgewar for starting this organization and appealed to Hindus all over India to open branches of this organization.[19]

Here we see an almost identical line of accusation, but shockingly, it isn't from the British. It comes from Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru wrote in a letter on 21 November 1947:

… [the] RSS is an injurious and dangerous organization and fascist in the strictly technical sense of the word. We have known about it for many years and some of our colleagues have been up against it for a long time. It is bad enough in Maharashtra where it originated. But the combination of RSS and Punjab has produced something worse. I have little doubt that we have to stand up against this … They are very well organised but extraordinarily narrow in their outlook and completely lacking in the appreciation of any basic problem.[20]

According to Gandhi’s private secretary, Pyarelal Nayar, whenever someone pointed out the good work of the RSS such as ‘refugee relief camps, showing discipline, courage, and capacity for hard work’, Gandhi used to respond by drawing the same parallel as the British did. Comparing the RSS with the Nazis. Gandhi used to respond with, ‘But don’t forget, even so had Hitler’s Nazis and the Fascists under Mussolini.’[21]

Because of the RSS’s disciplined social work and nationalist character, the British administration consistently branded the RSS as a ‘communal’ organisation. This colonial label, weaponised to divide Indian society, soon influenced sections of the Congress as well, leading them to repeat the same charge without scrutiny. It raises a striking question: why did the very organisation distrusted by the British Raj also become a target of suspicion for the Congress?

By the time of 1939, the Sangh had come under the surveillance of not just the provincial authorities but also the central government. On 11 July 1939, the Home Department at Simla dispatched a confidential note to the Chief Secretary of the provincial administration, consolidating all intelligence gathered on the RSS. The report stated that the Sangh’s objective was ‘to train Hindu youths to defend Hinduism and the Hindu community, and to inspire Hindus with a spirit of nationalism and self-confidence, to make them a great national force.’ The note summarized the key incidents of the preceding years to highlight the political, philosophical, and organizational characteristics:

The Sangh had been taking interest in the political movements of the country as a result of which the Central Provinces Government in their circular letter No. 2352-2158-IV, dated the 15/16th December 1932, felt it necessary to issue an order advising Government servants of the communal and political nature of this Sangh and, at the same time, forbidding them to become members or to participate in any of the activities of the organization. This roused the indignation of its chief sponsors, who gave vent to their feelings at the "Sankranti" celebrations on 10th January 1933. Dr Hedgewar asserted that the Government had acted on base insinuations made against the Sangh and denied that it was either a political or a communal body. Sir M.V. Joshi who presided, however admitted that it was a communal organization, but endeavoured to justify its existence in the interests of the Hindus, who he said must be able to defend themselves in times of need. He further said that the Sangh was opposed to the idea of non-violence. Dr Moonje went even further by favouring offence rather than defence and advocated a policy of "Strike first".[22]

By July 1939, Hedgewar’s health had deteriorated severely, forcing him to stay in a rented bungalow at Deolali near Nashik. Yet even as illness confined him, the movement he had founded was expanding with astonishing speed. A Special Branch report from this period reveals the scale of the Sangh’s growth: while the Central Provinces alone had nearly 9,000 members, more than 30,000 others had joined across various provinces, with around 350 shakhas operating nationwide. The report noted that the Sangh believed in cultivating physical strength and discipline, but, based on all available information, concluded that it ‘certainly does not seem to be an unlawful association’.[23]

By the time Dr. Hedgewar’s health finally gave way, he had already transformed the RSS from a modest gathering of a few young men in 1925 into a disciplined force of nearly 40,000 members by 1940. His passing on 21 June 1940 marked the close of a foundational era. From that moment onward, the task of leading, shaping, and expanding the Sangh fell to M. S. Golwalkar, the man millions would revere simply as Guruji.

When the Fourth Security Conference convened at Nagpur in March 1943, the British administration placed the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) on its formal agenda, a telling sign of how seriously the colonial state had begun to view the organisation. The minutes of the conference, apart from revealing the government's suspicion, offer a glimpse into how M.S. Golwalkar had managed the Sangh’s rapid expansion in the preceding years. To the government, the RSS had become a “potential danger.” It was catalogued as anti-British, exhibiting a pro-Japanese inclination in the wartime climate, and, in the eyes of the colonial intelligence machinery, its “fascist tendencies are obvious” in both conduct and organisation. Even as its network spread swiftly across provinces, drawing in increasing numbers of Hindu youth, British intelligence still could not fully decipher the deeper forces driving this surge. Yet on one point the government read the Sangh accurately: the RSS was clearly playing a long game. Golwalkar was steering the organisation away from open confrontation with the state, conserving its energies for a larger moment. The conference recorded this with cold precision: “It is felt that the true purpose of its being lies in the future, and that its revelation will be to the accompaniment of disorder.”[24]

The intelligence departments had gathered a considerable volume of information on the Sangh’s long-term intentions, yet they remained unsure how much of it could be trusted. But such ambiguity was hardly unusual, uncertainty is the permanent shadow of intelligence work, and every assessment carries within it a margin of doubt that must be calculated into policy. By 1939, however, one report stood out for its reliability. It stated that the Sangh’s leadership had reached a strategic decision: they would withdraw from overt political activity for the foreseeable future. Any premature plunge into the political arena, they believed, might expose the organisation to repression and threaten its very survival. Instead, the Sangh dedicated itself to a slower, deeper project, the ideological moulding of Hindu youth, training them for a future confrontation, a future struggle for India’s freedom as envisioned through the Sangh’s own ideological lens. The report said:

They had no faith in democracy and believed that freedom could only be won by violence. In 1940, it was reported that at the end of the annual forty day training selected members of the Sangh are as a rule, tried for a period of three years in different capacities and the most reliable of them are unobtrusively introduced into various departments of Government, such as the army, navy, postal, telegraph, railway and administrative services in order that there may be no difficulty in capturing control over the administrative departments in India when the time comes. This rather sensational inside account of the secret programme of the Sangh cannot be accepted literally, but it can be stated without exaggeration that the Sangh has been for some years working out a long-term policy of steady preparation for the attainment of its ultimate objective of Hindu supremacy.[25]

In December 1942, the Deputy Commissioner of Police in Jubbulpore (Jabalpur) reported that V. D. Savarkar’s call for Hindu youth to enlist in the ongoing war was not an act of loyalty to the British, but part of a deliberate long-term strategy. Savarkar viewed military recruitment as a rare opportunity for young Hindus to acquire discipline, training, and combat experience, resources that would later prove essential for a future revolution aimed at securing and safeguarding India’s independence. This objective, the report noted, was not immediate but strategic and time-bound, designed to mature only when circumstances were favourable. The report said:

It has been made sufficiently clear by the Hindu Sabhaites during the course of their usual talks that V.D. Sawarkar does not think that time was ripe for revolution in the country. The Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh organization, in the opinion of these leaders, which is yet to be sufficiently organized for the said purpose is likely to take every precaution to avoid its being brought to the notice of the Government adversely whereby the Government may not be able to declare the organization illegal or check its progress to the detriment of the interests of the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh. The organization as a whole remained aloof from the present subversive activities indulged in by the Congressmen.[26]

Meanwhile, Golwalkar was quietly forging a disciplined and tightly knit cadre, a network of volunteers trained to obey his command and prepared to assume any role he envisioned, even those the authorities feared might someday turn subversive. The Intelligence Bureau’s internal comparison between Golwalkar and Inayatullah Khan Mashriqi of the Khaksar movement is telling: Mashriqi was dismissed as an erratic, loud, and unstable megalomaniac, while Golwalkar emerged as the more dangerous figure, calm, calculating, and organizationally brilliant. Though the immediate threat posed by his activities seemed distant, the IB warned that leaving him unchecked could, in time, lead to the rise of a highly disciplined, ideologically driven force with the potential to disrupt public order on a far greater scale.[27]

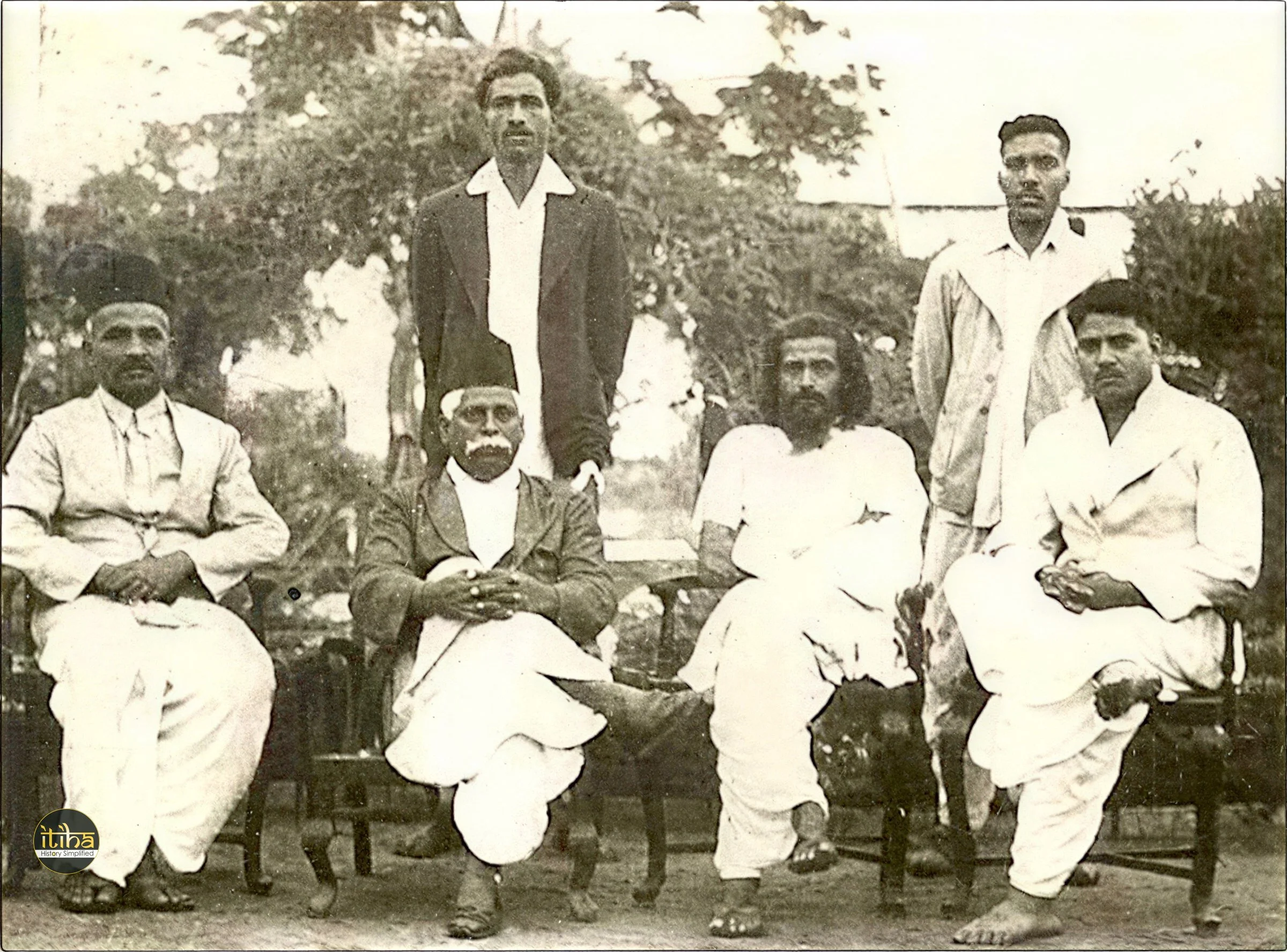

Hedgewar and his early followers during an RSS meeting in 1939

Congress members routinely lie by claiming that the RSS apologised to the British. The historical record says the exact opposite. The myth of Congress's “defiance” collapsed when prominent Gandhian followers were arrested for striking against the colonial government, their bravado evaporated within days. Nearly 200 of them hurriedly wrote apology letters to the British authorities, begging for release.[28]

Let us end with a fun fact: Pandit Nehru, a man deeply shaken, still reeling from India’s humiliating defeat at the hands of China in 1962, took a step few had imagined. In a moment that revealed both his vulnerability and the gravity of the national crisis, he invited the RSS to march in the 1963 Republic Day parade in Delhi.[29]

In response to Nehru’s invitation, a contingent of RSS volunteers in khaki marched in the 1963 Republic Day parade, an event that stunned many political observers. Nehru never explained how he came to rely upon, and even momentarily admire, an organization he had once virtually indicted for Gandhi’s assassination in 1948. Yet the reasons can be read clearly in the circumstances of the time and in the long shadow of the freedom struggle. Nehru had witnessed, with helpless anguish, how Gandhi’s creed of absolute non-violence and his insistence on ‘Hindu–Muslim unity at any cost’ had failed to prevent the ghastly bloodshed of Partition. And now, in 1962, he stood devastated by another blow, India’s crushing defeat at the hands of China, a defeat born largely of his own idealistic underestimation of defence preparedness. The RSS, by contrast, had consistently preached self-discipline, preparedness, and the necessity of strong self-defence against aggression. For years, its volunteers had offered their services in situations of internal disorder, often at moments when the state itself appeared unready. The RSS volunteers played an important role and, despite having big ideological differences, backed the war efforts of the Nehru government.[30] In the grim aftermath of 1962, Nehru, a shattered statesman confronting the consequences of his pacifist convictions, seems to have recognized the value of a force he had long dismissed. And so, for the first and only time, the RSS was invited to march down Rajpath, its disciplined ranks reflecting a philosophy the prime minister could no longer ignore.[31]

Citations

[1] Chandrachur Ghose, ‘Many Shades of Saffron’, (2025), pp.11-12.

[2] Ibid., p.12.

[3] Rakesh Sinha, ‘Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar’, pp.8-11. Quoted from Chandrachur Ghose, ‘Many Shades of Saffron’, (2025), p.12.

[4] N.H. Palkar, ‘Man of the Millennia-Dr. Hedgewar’, Kindle Edition. p.25. Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p.57. Ibid.15

[6] Rakesh Sinha, ‘Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar’, p.18. Ibid.

[7] Ibid., pp. 57-66. Ibid.

[8] Bhupat Majumdar, ‘Agnijuger Onyotomo Nayak Dr Hedgewar', pp. 13-17. Ibid.16

[9] Calcutta Records 1-1912, Home Department, Proceedings, April 1912, nos.136-139, National Archives, New Delhi. Ibid.

[10] Walter Andersen, The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh 1: Early Concerns. Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 7, No. 11, 1972, pp. 589+591-97. Ibid.18

[11] Rakesh Sinha, ‘Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar’, p.33-34. Ibid.

[12] Ibid. p.35. Ibid.

[13] Ibid. pp.43-44. Ibid.29

[14] Ibid. pp.64-65. Ibid.34

[15] Ibid. pp. 66-71. Ibid.36

[16] N.H. Palkar, ‘Man of the Millennia-Dr. Hedgewar’, Kindle Edition. pp. 310-311. Ibid.52

[17] Sachin Nandha, Hedgewar: A Definitive Biography, p. 35. Ibid.

[18] Fortnightly Reports on the Internal Political Situation for the Month of October 1932, Home Department, Government of India, File No. 18/13/32 Poll, National Archives, New Delhi. Ibid. p.58

[19] File No. 22/55/35-Political, Home Department, National Archives, New Delhi. Ibid. p.66

[20] Nehru’s letter to Dalip Singh, 21 November, 1947, SWJN, series 2, vol. 4, pp. 330–333.

[21] Pyarelal Nayar, Mahatma Gandhi: The Last Phase, Vol 2, p.440.

[22] Request by the C.P. Government for Notes on the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh and the Khaksara Movement, File No. 92/39 Poll, Home Department, Government of India, National Archives, New Delhi. Quoted by Chandrachur Ghose, ‘Many Shades of Saffron’, (2025), pp.76-77.

[23] Information regarding the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh, the Khaksar movement and the question of taking action against them, File No. 289, Govt of the Central Provinces and Berar, National Archives, New Delhi. Ibid. p.78-79.

[24] Note on the organization, aims etc. of the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Singh File No. 28/8/42-POLL (I), Government of India, Home Department, National Archives, New Delhi. Ibid.p.89-90

[25] Ibid. Ibid.90-91.

[26] Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh: Organization and Development in Each District of C.P. and Berar at the End of the Year 1942, KW to FN 28/3/1945, Home Department, Government of India, National Archives, New Delhi. Ibid. p.102.

[27] Activities of the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh, File No. 28/3/43-Poll (3). Home Department, Government of India, National Archives, New Delhi. Ibid. p103.

[28] Rajmohan Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p.115.

[29] M.G. Chitkara, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh: National Upsurge, APH Publishing Corporation, 2004, p.275.

[30] https://www.firstpost.com/india/right-word-how-the-eternal-backroom-boys-of-rss-played-stellar-role-in-nation-building-11056551.html

[31] M.S. Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, p.224.