Drafts Which Shaped the Indian Constitution

The Swaraj Bill of 1895

"Swaraj is my birthright." - Bal Gangadhar Tilak

The first non-official initiative to draft a Constitution for India incorporating a parliamentary system of government was undertaken in 1895 under the inspiration of Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak. In a brief preface to what he described as a “Home Rule Bill” (Swaraj Bill),[1] Tilak outlined the framework of a Constitution that he envisioned India would obtain from the British Government. This proposed document, titled the Constitution of India Act, envisaged the establishment of a Parliament of India, defined as an assembly comprising both official and non-official representatives of the Indian nation.

The proposed Parliament was to function as a forum in which every citizen could freely express opinions through speech or writing and publish them without fear of censorship or penalty, subject only to accountability for any abuse of this right. It further affirmed the principle that no individual should be punished except by a competent authority and that the law should apply equally to all citizens. The draft also provided for universal voting rights, granting every citizen one vote for the election of members of Parliament and one vote for the election of members of the local legislative councils. The document was drafted in a formal legal style and comprised 110 articles.[2]

Historical Context: Nationalism’s Constitutional Stirrings

The Swaraj Bill arrived at a pivotal moment. The Indian National Congress, founded in 1885, was evolving from a platform for moderate reforms to a voice demanding greater self-governance. Influenced by British liberal ideals and global democratic experiments, like the U.S. Bill of Rights and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, the bill rejected outright independence but sought dominion status within the British Empire. Its preamble invoked the “Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty” while asserting that sovereign, legislative, judicial, and executive powers were “delegated by the Nation” and vested in a Parliament of India. This hybrid vision reflected the era’s pragmatism: loyalty to the Crown paired with an unyielding call for Indian agency.

At its core, the bill’s emphasis on fundamental rights (outlined in Sections 13–26) was revolutionary. These provisions were not mere appendages but the bedrock of citizenship, ensuring that individual liberties underpinned the state’s structure. In an age when Indians were subjects rather than citizens, denied basic political rights under the Indian Councils Act of 1892, the bill’s declaration that “the law shall be equal to all” (Section 20) stood as a defiant rebuke to colonial hierarchies based on race, caste, and creed.

Fundamental Rights: Pillars of Liberty and Dignity

The Swaraj Bill’s fundamental rights section reads like a manifesto for human dignity, predating similar enumerations in 20th-century constitutions. Spanning Sections 13–26, these rights were framed as inherent to Indian citizenship, applicable to all born in India, children of Indian parents (even abroad under certain conditions), or naturalized foreigners. Loss of these rights was narrowly circumscribed, through naturalization abroad, acceptance of foreign honors without license, or criminal sentences, ensuring protections were not easily revoked.

Some sections of the bill are worth mentioning:

Participation in Governance (Section 13): “Every citizen has a right to take part in the affairs of his country.” This democratic cornerstone allowed citizens to engage via means prescribed by Parliament, foreshadowing universal suffrage.

Right to Bear Arms (Section 14): Citizens were “required to bear arms, to maintain and defend the Empire against its internal and external enemies.” While tied to imperial defense, this affirmed a collective duty to national security, empowering individuals as active protectors rather than passive subjects.

Rule of Law (Section 15): “No citizen shall do, or omit to do, any act unless by virtue of law.” This enshrined the principle that all actions must align with legal bounds, preventing arbitrary state overreach.

Freedom of Expression (Section 16): “Every citizen may express his thoughts by words or writings, and publish them in print without liability to censure, but they shall be answerable for abuses, which they may commit in the exercise of this right, in the cases and in the mode the Parliament shall determine.” A balanced safeguard against sedition laws, it protected speech while allowing parliamentary regulation—progressive for its time.

Personal Security and Privacy (Sections 17–19): Homes were declared “inviolable asylums,” no one could be imprisoned without a “special crime proved against him according to law,” and sentencing required “competent authority.” These clauses directly challenged colonial practices like warrantless searches and indefinite detention.

Right to Property and Petition (Sections 23–24): Citizens enjoyed “right of property to its fullest extent, except where the law determines otherwise,” and could “present to his Sovereign or to the Parliament... claims, petitions and complaints.” Property as a fundamental entitlement countered land revenue exploitations, while petition rights democratized access to justice.

Education as a Right (Sections 25–26): “State Education shall be Free in the Empire” and “Primary Education shall be Compulsory.” This visionary mandate aimed to uplift the masses, recognizing education as essential for equality.

Voting rights (Section 29) further democratized these liberties: “Every citizen has a right to give one vote for electing a member to the Parliament of India and one to the Local Legislative Council.” Though limited by qualifications like age (25) and citizenship tenure (10 years), it marked a leap toward representative rule.

Equality: The Bill’s Beating Heart

Amid these rights, equality emerges as the bill’s moral and legal fulcrum, articulated succinctly yet powerfully in Section 20: “The law shall be equal to all.” This clause was no platitude; it was a radical assertion in a society stratified by British racial policies, princely privileges, and the caste system. The bill’s equality provision demanded uniform application of laws, prohibiting exemptions based on status, a direct antidote to the discriminatory Ilbert Bill controversies of the 1880s, where European settlers resisted equal legal treatment for Indian judges.

This equality extended beyond the courtroom. Section 21 guaranteed that “every citizen may be admitted to public office,” dismantling barriers to bureaucratic and political participation. Taxation was proportional to “substance” (Section 22), ensuring fairness in burdens. Religious tolerance was absolute: “All religions and modes of worship are permitted,” fostering a secular ethos that tolerated diversity without favoritism. In essence, the bill’s equality was substantive, intertwining with rights to create a framework where liberty was meaningless without fairness.

Though the Swaraj Bill never saw enactment, overshadowed by escalating colonial resistance and the rise of more radical movements, its imprint endures. It influenced subsequent drafts, including the Nehru Report of 1928, and resonated in the Constituent Assembly debates of 1946–1949. The modern Indian Constitution’s Part III (Fundamental Rights) mirrors its spirit: Article 14’s “equality before the law” echoes Section 20 verbatim in intent, while freedoms of speech (Article 19) and religion (Article 25) build on its foundations.

The 1895 bill reminds us that India’s constitutional story began not in 1950 but in the audacious imaginations of late-19th-century patriots. By prioritizing fundamental rights and equality, it transformed Swaraj from a slogan into a blueprint.

"Simon Go Back" was a protest slogan used in 1928 against the all-British Simon Commission sent to India to report on constitutional reforms. Indians, led by Congress and other leaders, boycotted the commission because it excluded Indian members, viewing it as an insult to their sovereignty.

The Simon Commission

"Simon Go Back" - Yusuf Meherally

The Simon Commission, appointed by the British government in November 1927 under the leadership of Sir John Simon, was tasked with evaluating the efficacy of the Government of India Act of 1919, commonly known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, and proposing subsequent constitutional advancements. Notably, the commission comprised exclusively British members, a composition that conspicuously omitted any Indian representation.

The formation of the Simon Commission can be attributed to several factors. The 1919 Act had stipulated a review of constitutional developments after a decade, which would have occurred in 1929. However, the British administration preemptively initiated this assessment in 1927, primarily to circumvent conducting it under a prospective government perceived as more amenable to Indian nationalist aspirations. Furthermore, the entirely British makeup of the commission disregarded Indian demands for inclusion in deliberations concerning their own governance.

The Indian response to the Simon Commission was marked by profound indignation, as the exclusion of Indian members was interpreted as a profound affront to national dignity and self-determination. This sentiment precipitated widespread agitation across the subcontinent, manifesting in protests, strikes, black-flag demonstrations, and hartals. The evocative slogan "Simon Go Back!" emerged as a unifying emblem of resistance. Key figures, such as Lala Lajpat Rai, spearheaded these demonstrations and endured severe police brutality; Rai succumbed to injuries inflicted during one such confrontation.

In terms of its broader implications for discourses on rights, the Simon Commission represented a pivotal juncture, emblematic of the British imperial reluctance to acknowledge Indian political autonomy. This backlash compelled Indian leaders to assert initiative independently, culminating in the formulation of the Nehru Report in 1928.

Karachi Resolution (1931)

In March 1931, merely six days following the execution of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, and Rajguru, the Indian National Congress convened and adopted the Karachi Resolution, which had been drafted by Jawaharlal Nehru. This resolution expanded the concept of "Swaraj" beyond mere political independence to encompass social and economic freedoms as well.

The Karachi Resolution incorporated two principal components. The first outlined fundamental rights, which included protections for freedom of speech, equality before the law, and the safeguarding of civil liberties. The second component presented a national economic program that emphasized social and economic justice, advocating measures such as the right to work, a minimum wage, protections for workers and peasants, and state ownership or control of key industries.

The significance of the Karachi Resolution lies in its role as the inaugural comprehensive framework for the rights and socio-economic policies of an independent India. Furthermore, it served as a foundational influence for the Directive Principles of State Policy enshrined in Part IV of the Indian Constitution.

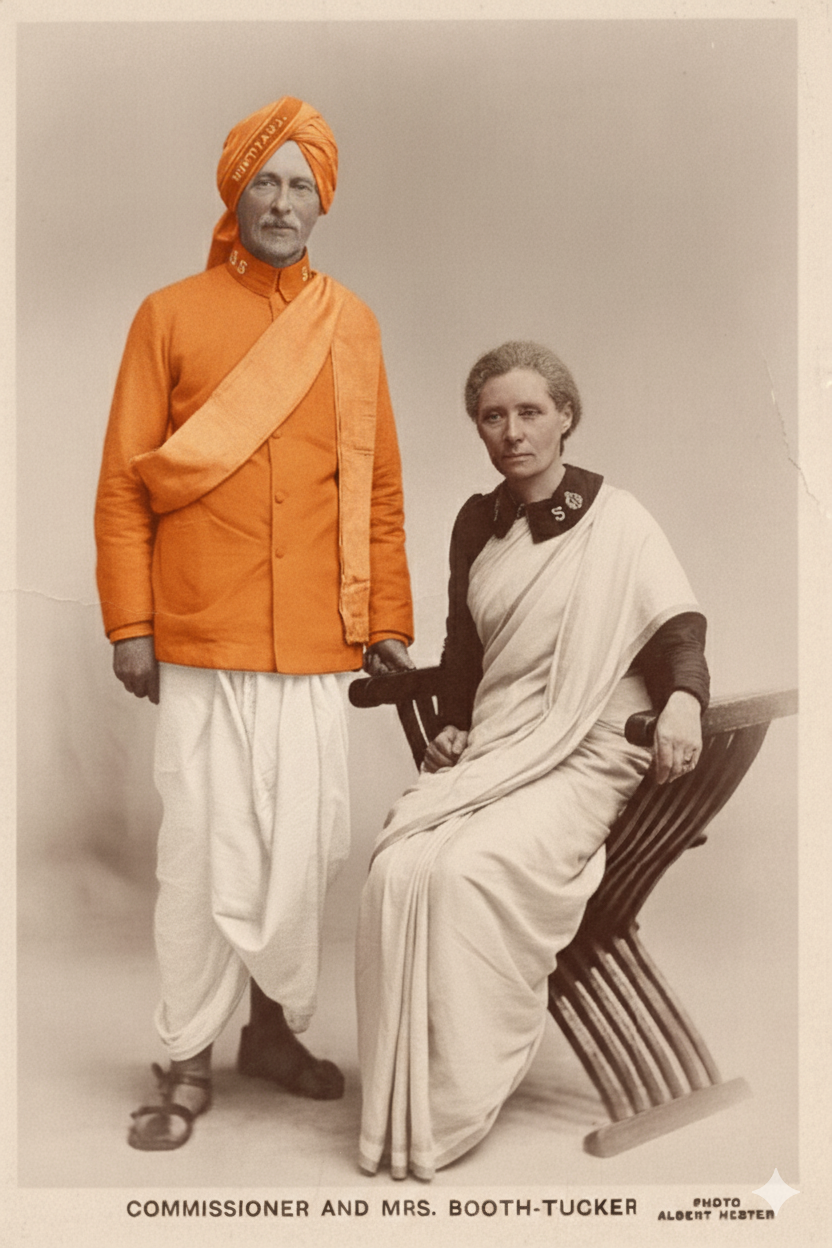

Sir Benegal Narsing Rau CIE was an Indian civil servant, jurist, diplomat and statesman known for his role as the constitutional advisor to the Constituent Assembly of India. He was also India's representative to the United Nations Security Council from 1950 to 1952.

Draft Constitution of India 1948

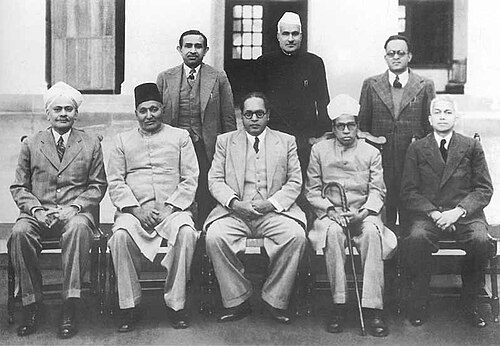

By October 1947, B. N. Rau had prepared the first draft of India’s Constitution. During two and a half years of intense debate and discussion in the Constituent Assembly, the Constitution of India was ultimately finalized on 26 November 1949. On 21 February 1948, the Drafting Committee submitted the Draft Constitution of India to the President of the Constituent Assembly. Four months earlier, the Committee had received a preliminary draft prepared by the Assembly’s Constitutional Adviser, Sir B.N. Rau. This document reflected the Assembly’s earlier decisions, based on reports from various subcommittees entrusted with framing specific constitutional provisions. Between October 1947 and February 1948, the Drafting Committee, under the chairmanship of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, carefully examined, refined, and expanded upon Rau’s draft. The outcome of this process was the Draft Constitution of India, 1948.

The Draft comprised 315 Articles arranged across eighteen Parts and eight Schedules. It covered a broad spectrum of constitutional themes, including the structure of government, Centre–State relations, and the fundamental rights of citizens. In sections where the Drafting Committee made major revisions to Rau’s text or where ambiguities persisted, it inserted explanatory notes and footnotes to clarify its reasoning.

Notably, this Draft was the first comprehensive blueprint of the Indian Constitution to be made publicly available. It was circulated widely among Assembly members, provincial governments, central ministries, the Supreme Court and High Courts, as well as the general public, accompanied by an invitation for feedback and suggestions. After reviewing the comments received in March and October 1948, the Drafting Committee incorporated necessary amendments.

On 4 November 1948, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar formally introduced the revised Draft Constitution in the Constituent Assembly. Each member was provided with a copy of the document, along with the set of amendments recommended by the Committee. In his introductory address, Ambedkar summarized the contents of the Draft and responded to certain criticisms that had surfaced during the consultative process. Reactions within the Assembly were mixed, while some members lauded the Draft as a remarkable achievement, others expressed disappointment, particularly over its limited emphasis on the principles of Panchayati Raj in shaping India’s administrative and political framework.

On 15 November 1948, the Constituent Assembly commenced the clause-by-clause consideration of the Draft Constitution. Each provision was subjected to detailed debate, scrutiny, and amendment. Over the following eleven months, the Assembly discussed and decided upon numerous proposals and modifications introduced both by individual members and by the Drafting Committee itself. This extensive deliberative process continued until 17 October 1949. Subsequently, the Drafting Committee incorporated the Assembly’s decisions and prepared a revised version of the Draft Constitution, which was submitted for a second reading on 14 November 1949.

The discussions surrounding the Draft Constitution, along with its revised version, constituted the core of the Constituent Assembly Debates and represented the most substantial phase of India’s constitution-making process. Out of the Assembly’s total 165 sittings, an impressive 114 were devoted exclusively to debating this Draft. Finally, after nearly three years of exhaustive deliberation, the Constituent Assembly adopted the Draft Constitution on 26 November 1949, enacting it as the Constitution of India. Often, it is Dr. Ambedkar who is credited for adding the Fundamental Rights and Abolition of “Untouchability,” but we get to see these rights in the first draft of the Constitution, which was done by B.N. Rau, who was also a Brahmin by birth. The following are the Articles of the Draft Constitution of India 1948, which abolished Untouchability and added Fundamental Rights:

PART III

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

Rights of Equality

DC.9

9. (1) The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex or any of them. In particular, no citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex or any of them, be subject to any disability, liability, restriction or condition with regard to-

(a) Access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and places of public entertainment, or

(b) The use of wells, tanks, roads, and places of public resort maintained wholly or partly out of the revenues of the State or dedicated to the use of the general public.(2) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any special provision for women and children.DC.10

10. (1) There shall be equality of opportunity for all citizens in matters of employment under the State.

(2) No citizen shall, on grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth or any of them, be ineligible for any office under the State.

(3) Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favour of any backward class of citizens who, in the opinion of the State, are not adequately represented in the services under the State.

(4) Nothing in this article shall affect the operation of any law which provides that the incumbent of an office in connection with the affairs of any religious or denominational institution or any member of the governing body thereof shall be a person professing a particular religion or belonging to a particular denomination.DC.11

11. “Untouchability” is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any disability arising out of “Untouchability” shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law.[3]

Dr. Ambedkar also gave credit to Sir B.N. Rau:

The credit that is given to me does not really belong to me. It belongs partly to Sir B.N. Rau, the Constitutional Adviser to the Constituent Assembly who prepared a rough draft of the Constitution for the consideration of the Drafting Committee. A part of the credit must go to the members of the Drafting Committee who, as I have said, have sat for 141 days and without whose ingenuity of devise new formulae and capacity to tolerate and to accommodate different points of view, the task of framing the Constitution could not have come to so successful a conclusion. Much greater, share of the credit must go to Mr. S.N. Mukherjee, the Chief Draftsman of the constitution. His ability to put the most intricate proposals in the simplest and clearest legal form can rarely be equalled, nor his capacity for hard work. “He has been as acquisition to the Assembly. Without his help, this Assembly would have taken many more years to finalise the Constitution. I must not omit to mention the members of the staff working under Mr. Mukherjee. For, I know how hard they have worked and how long they have toiled sometimes even beyond midnight. I want to thank them all for their effort and their cooperation. (Cheers.)[4]

Just as Dr. Ambedkar did, Mr. K.M. Munshi also gave credit to B.N. Rau, K.M. Munshi was an Indian freedom fighter, lawyer, writer, and educationist who played a crucial role in the independence movement and the formation of modern India. He was also member of the Constituent Assembly Debates, and he said this about Sir B.N. Rau:

The Members of the Committee, I may mention, have devoted careful attention to every aspect of the Rules and we have had the assistance of the able and distinguished jurist, our Constitutional Adviser, Sir B.N. Rau. The Committee had done its best to give it as perfect a shape as is possible. But I dare say there may be many defects still left, and the House may find some discrepancies. I am sure, points of view may have been omitted; I seek therefore the indulgence of the House. These are the Rules of the Assembly. They can be altered or added to when we next meet. We can always add new points of view if some one are omitted. But it is highly essential that we should adopt the Rules and appoint one or two committees which would keep the organisation of the Constituent Assembly going.[5]

Jaspat Roy Kapoor was a lawyer, a congressman, and a member of the Constituent Assembly Debates also gave credits to B.N. Rau, he said:

I must also express my gratitude to Shri B.N. Rau, Mr. Mukherjee and his loyal lieutenants for the very good and efficient work that they have all done. Shri B.N. Rau kept on flooding on us precedents after precedents of Constitutions as they are in the different parts of the world and they have been very helpful to us.[6]

Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar was the chairman of the Credential Committee of the Constituent Assembly of India. He served as the Advocate General of Madras State from 1929 to 1944, he said:

I would also be failing in my duty if I do not give my tributes to the services of Sir B.N. Rau and to the untiring energy, patience, ability and industry of the Joint Secretary, Mr. Mukherjee and his lieutenants.[7]

The World’s Longest Surviving Written Constitution

“However good a constitution may be, if those who are implementing it are not good, it will prove to be bad. However bad a constitution may be, if those implementing it are good, it will prove to be good.” - Dr. Ambedkar

The journey began with the Constituent Assembly, formed in 1946 under the Cabinet Mission Plan. Comprising 299 members (after the partition reduced it from 389), the Assembly held its first session on December 9, 1946. Over 2 years, 11 months, and 17 days, it conducted 11 sessions, debating every clause meticulously. Dr. Ambedkar played a pivotal role, guiding the debates and ensuring the document reflected principles of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity.

The Indian Constitution is the longest written constitution in the world. At the time of its adoption in 1950, it contained 395 Articles, 22 Parts, and 8 Schedules. Over time, amendments have expanded it further, reflecting India’s evolving needs. Its detailed nature was intentional, aimed at addressing the complexities of a vast and diverse nation. Unlike most modern constitutions, the original Indian Constitution was entirely handwritten in both English and Hindi. It was calligraphed by Prem Behari Narain Raizada and artistically decorated by Nandalal Bose and his students from Shantiniketan. Each page is a blend of law and art, showcasing India’s rich heritage. The Indian Constitution is often described as a “bag of borrowings”, but this borrowing was deliberate and thoughtful. It adopted the best features from various constitutions across the world, Fundamental Rights from the USA, Parliamentary Government from the UK, Directive Principles from Ireland, and Federalism from Canada. This fusion created a uniquely Indian constitutional framework.

Delivering a lecture on India’s Constitution at the University of Madras in 1951, Sir Ivor Jennings described it as: ‘Too long, too rigid, too prolix’, and said that the dominance in the Constituent Assembly of lawyer-politicians had contributed to its complexity! In fact, he characterized India’s Constitution as ‘a truly oriental display of occidental constitutional devices.’[8] The same Ivor Jennings had been entrusted with the task of drafting the Constitution of Ceylon (now, Sri Lanka); and he took great care to see that it endured, but it lasted only fourteen years, which only goes to show that a finely-worded document is no guarantee of its success. It is only a spirit of constitutionalism (amongst the representatives of the people) that helps to keep it alive and functioning.[9]

ENDNOTES

[1] One can access the bare act here https://www.constitutionofindia.net/historical-constitution/the-constitution-of-india-bill-unknown-1895/

[2] B. Shiva Rao, Framing of India’s Constitution: Select Documents, Vol. I, pp.5-15.

[3] https://www.constitutionofindia.net/committee-report/draft-constitution-of-india-1948

[4] Dr. Ambedkar’s Last Speech in the Constituent Assembly on the Adoption of the Constitution. (November 25, 1949), p. 329.

[5] Constituent Assembly Debates (Proceedings) (9th December,1946 to 24th January,1950. pdf p. 226.

[6] Ibid., pdf p. 6509.

[7] Ibid., pdf p. 6576.

[8] Sir Ivor Jennings (1903-1965), British lawyer and academic who served as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ceylon (1942-1955) and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge (1961-1963). Jennings was an authority on constitutional law, and author of a definitive book on the workings of the unwritten British Constitution. He had advised in the drafting of the Constitution of Ceylon to form the Dominion of Ceylon. Quoted from Fali S Nariman, You Must Know Your Constitution, p.16.

[9] Playwright George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950) visited Ceylon in 1948 – and he was ecstatic about its people. This is what he wrote to Jawaharlal Nehru: “I was convinced that Ceylon is the cradle of the human race because everybody there looks an original. All other nations are obviously mass produced.”! (Typically Shavian). Ibid.

The Great Escape of Netaji

In the annals of India’s struggle for independence, few episodes are as cinematic and daring as the "Great Escape" of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. While the British Raj believed they had the "rebel" leader securely confined within the walls of his Elgin Road residence in Calcutta, Bose was busy orchestrating a vanishing act that would shift the theater of his revolution from the streets of Bengal to the global stage of World War II.

Based on the historical records preserved by the Netaji Subhas Bose organization and archival accounts, here is the story of that perilous journey. By late 1940, the British government had placed Subhas Chandra Bose under strict house arrest. Following his release from prison on medical grounds after a hunger strike, he was confined to his father’s bedroom at 38/2 Elgin Road. A ring of secret police and intelligence officers surrounded the house 24/7, monitoring every visitor and movement. By that time, Netaji had reached a definitive conclusion that he could not win India's freedom with the Congress/Gandhian ways.

To the outside world, Bose was a broken man, seeking solace in prayer and meditation. He grew a long beard, remained in seclusion, and let it be known that he was considering a life of renunciation as a sadhu. In reality, this was the "bluff of religious seclusion", a psychological smoke screen designed to lower the guards’ vigilance. Certain historical accounts suggest that Savarkar proposed to Netaji the strategy of initiating an armed revolution from abroad.

On 22 June 1940, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose met Savarkar at Savarkar Sadan in Mumbai.

In this meeting, it is said that Savarkar advised Netaji to establish India’s own armed force to fight against the British.

Background: The Road to House Arrest

To understand the escape, we must first contextualize Bose's predicament. Subhas Chandra Bose, born in 1897, was a fiery nationalist whose vision for India's independence diverged sharply from the non-violent path advocated by Mahatma Gandhi. By 1940, Bose had already served as the President of the Indian National Congress twice, but his radical views led to conflicts within the party. He founded the Forward Bloc in 1939, emphasizing armed struggle and socialist principles. The British colonial authorities, wary of his influence, arrested him on December 5, 1940, under the Defense of India Rules. Initially imprisoned, he was transferred to his family residence at 38/2 Elgin Road in Calcutta (now Kolkata) for health reasons, but this was no lenient measure; it was house arrest under strict surveillance. The house, a spacious colonial-era bungalow, became both a prison and a planning ground.

Surrounded by 62 sleuths from the British intelligence, every visitor was monitored, mail intercepted, and movements scrutinized. Bose's health had deteriorated due to a hunger strike in jail, but his mind remained sharp. During his 40 days at home, he immersed himself in spiritual practices, including prayer, meditation, and reading the Bhagavad Gita in his father's bedroom. This period of apparent quiescence masked intense internal deliberations. Bose realized that remaining in India would lead to prolonged imprisonment, stifling his ability to organize resistance. He believed the ongoing World War II presented opportunities to align with Britain's enemies, initially Russia or Japan, to wage an armed struggle from abroad.

Bose's correspondence during this time reveals his frustrations. On December 29, 1940, he wrote to Gandhi, offering cooperation despite their ideological differences. Gandhi's reply was telling: "You are irrepressible whether ill or well. Do get well before going in for fireworks." He added, "With the fundamental differences between you and me, it is not possible till one of us is converted to the other's view, we must sail in different boats, though their destination may appear, but only appear to be the same." This exchange underscored Bose's isolation within the mainstream Congress leadership and solidified his resolve to escape.

The Meticulous Planning Phase

Planning the escape was a clandestine operation involving a network of trusted allies. Bose drew on contacts from the Kirti Kisan Party, including Sardar Niranjan Singh Talib and Comrade Acchar Singh, but arrests disrupted early efforts. The Bengal Volunteers, a revolutionary group, took the lead under Major Satya Gupta and Satya Ranjan Bakshi, who handled logistics and funding. Bose's niece, Ila Bose, played a pivotal role in coordinating within the family.

The escape route was charted via Peshawar to Kabul, Afghanistan, a treacherous path through the North-West Frontier Province, known for its rugged terrain and tribal conflicts. This choice was strategic: Afghanistan was neutral, offering potential gateways to Russia or Europe. To evade detection, Bose would disguise himself as Mohammed Zia-ud-din, an insurance agent from the United Provinces. The plan required precise timing, as a court hearing was scheduled for January 16, 1941. Bose feigned illness to secure a medical extension; his family doctor, Dr. Sunil Bose, refused to issue a certificate, deeming it unethical, but Dr. Mani De stepped in, later facing humiliation from the authorities for his involvement.

Family members were selectively involved to maintain secrecy. Bose's nephews Dwijendra and Aurobindo, along with Ila, assisted in preparations. His brother Sarat Chandra Bose was kept in partial confidence. Crucially, Dr. Sisir Kumar Bose, Sarat's son and a medical student uninvolved in politics, was chosen as the driver due to his efficiency and familiarity with the family's Wanderer car. Sisir had scouted alternative routes to avoid police checkpoints. Bose deceived even his closest kin by pretending to accept impending jail time, ensuring no suspicions arose.

Funds were arranged discreetly, and contingencies were planned for the journey ahead. Mian Akbar Shah, a Forward Bloc leader from the North-West Frontier, visited Bose on December 16, 1940, to finalize the Peshawar-Kabul leg. Shah would meet Bose in Peshawar and arrange escorts. The plan's success hinged on slipping past the surveillance net around the Elgin Road house—a feat that seemed impossible given the 62 agents stationed there.

The Night of the Escape

January 16, 1941, marked Bose's last public appearance at home. As evening fell, the house buzzed with normalcy, but tension simmered beneath. Around 1:30 AM on January 17, Bose, disguised in a long coat, pajamas, and a fez cap as Mohammed Zia-ud-din, bid a quiet farewell to his family. With the help of his nephews, he exited through a side door, evading the watchful eyes outside. Sisir Bose waited in the Wanderer car, engine humming softly.

The drive was nerve-wracking. They headed northwest towards Bararee in Bihar, a distance of about 250 miles, navigating dark roads and potential checkpoints. To maintain the ruse, they posed Zia-ud-din as a traveling insurance agent. Upon reaching Bararee, they rested at the home of Dr. Asoke Nath Bose, another nephew. Here, the deception continued: servants were told Zia-ud-din was a visitor from Calcutta, preventing any leaks.

From Bararee, Sisir drove Bose to Gomoh railway station, where he boarded the Delhi Kalka Mail train under his alias. This leg was critical; any recognition could unravel the plan. Bose arrived at Peshawar Cantonment on January 19, 1941. Mian Akbar Shah met him and escorted him via tonga (horse-drawn carriage) to the Taj Mahal Hotel, then to the home of Abad Khan, a trusted ally.

The escape from the house was a masterstroke of timing and disguise. Back in Calcutta, Bose's absence wasn't immediately noticed. His mother, Prabhavati Devi, feigned ignorance when police inquired, demanding to know what they had done with her son. The British concocted a story of Bose renouncing worldly life, but it was widely disbelieved. Poet Rabindranath Tagore expressed public concern, amplifying the sensation.

The Journey Through India: To the Frontier

With the house escape successful, the real perils began. In Peshawar, Bose faced a language barrier—he couldn't speak Pushtu, the local tongue. To blend in, he adopted the guise of a deaf-mute Pathan, complete with traditional attire. Mian Akbar Shah assigned Bhagat Ram Talwar, a communist and Forward Bloc sympathizer (posing as Rahmat Khan), as his escort. They portrayed Bose as an elderly relative seeking a cure at the Adda Sharif shrine.

On January 19, they left Peshawar by car towards Jamrud, the gateway to the tribal areas. The next day, they detoured to Garhi village on foot, where they were joined by armed Pathan bodyguards for protection. The North-West Frontier was a lawless region, rife with tribal feuds and British patrols. On January 26, 1941—India's Republic Day in modern times—they crossed into tribal territories beyond British control.

The trek covered over 200 miles of rugged terrain, mountains, rivers, and deserts, often on foot, with minimal food and rest. They stayed at the Adda Sharif Dargah, where the Pir provided shelter and rotated bodyguards. Reaching Lalpura by 9 PM one evening, they found refuge with an influential Khan who furnished a Persian letter of introduction: "Rahamat Khan and Ziauddin were residents of Lalpura and were going to the Dargah of Sakhi Saheb." This document proved invaluable when a harassing CID constable in Kabul Serai demanded bribes, taking Bose's gold wristwatch, a family heirloom from his father, Janaki Nath Bose.

Crossing the Kabul River posed another challenge. Without a boat, locals improvised a vessel from inflated leather sacks. The route bypassed Daka to avoid octroi duties, adding to the hardship. Near Thandi, exhaustion overtook Bose; he slept roadside while Rahmat flagged down vehicles. A lumbering lorry laden with goods finally stopped—they clambered atop, enduring freezing winds, snow, and whipping branches. Stops for tea provided a brief respite. At Batghake, they paid duties and bribes, leveraging the Khan's letter, arriving in Kabul Serai by late afternoon on January 31, 1941.

Perils in Kabul: Hiding and Diplomacy

Kabul was a den of intrigue, with spies from various powers. Language barriers compounded issues, Rahmat spoke only Pushtu, not Persian. They initially lodged in a dingy sarai near Lahori Gate, a filthy area teeming with potential informers. Bose's goal was Russian assistance, banking on Soviet sympathy for anti-colonial struggles and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Efforts to contact the Soviet ambassador faltered; they located the embassy but couldn't gain entry. Days of waiting culminated in stopping the ambassador's car, only to face skepticism.

Dejected, Bose turned to the German minister, Hans Pilger, via Indian bazaar contacts. Pilger, suspecting a British trap (possibly fueled by Communist Party of India agents), involved Berlin and the Italian embassy. Living conditions deteriorated; Bose fell ill in the unsanitary sarai and bribed a suspicious Afghan policeman with Rs 10, then his wristwatch. By mid-February, Rahmat secured shelter with Uttamchand Malhotra, a radio repairman in the Indian neighborhood. A nosy neighbor nearly exposed them, prompting a temporary relocation.

On February 22, 1941, Bose met Italian Ambassador Pietro Quaroni, who described him as "intelligent, able, full of passion, and without doubt the most realistic, the only realist among Indian nationalist leaders." Multiple meetings explored exit strategies. British intelligence intercepted an Italian telegram on February 27, alerting them to Bose's presence. Declassified documents reveal a British order on March 7, 1941, to assassinate Bose via Middle East operatives. Undeterred, Bose wrote articles like "Gandhism in the Light of Hegelian Dialectic" and "A Message to My Countrymen," entrusting them to Rahmat for delivery to Calcutta.

By March 3, Moscow approved a transit visa. On March 10, Bose's photo was inserted into Italian diplomat Orlando Mazzotta's passport. He handed a political thesis and a letter to his brother Sarat to Rahmat. On March 18, 1941, Bose departed Kabul by car with two Germans and one Italian, traversing the Hindu Kush mountains to Samarkand, then by train to Moscow (arriving March 27 or 31, per accounts), and finally by air to Berlin on March 28.

The Frontier's Wild Tribes

The Afghan frontier, with its Pathan tribesmen and unforgiving landscapes, tested Bose's endurance. This region, depicted in historical accounts as a hotbed of resistance against colonial forces, required navigating tribal loyalties and natural hazards. Bose's adoption of Pathan customs and silence as a "deaf-mute" was a clever adaptation, but the physical toll, cold nights, hunger, and constant vigilance were immense.

Bhagat Ram Talwar, Bose's escort, later emerged as a complex figure, a quintuple spy working for multiple powers. While crucial to the escape, he allegedly betrayed related rebellion plans, leading to arrests and tragedies among Bose's allies.

Arrival in Germany and the Aftermath

In Berlin, Bose was sheltered by the German Foreign Office under Dr. Adam von Trott zu Solz, a non-Nazi who later joined anti-Hitler plots. Bose established the Free India Center, recruited aides, and began broadcasts. He met Joachim von Ribbentrop and Adolf Hitler, pushing for Axis support for Indian independence. The Indian Legion was formed from POWs, and plans for sabotage unfolded. The escape's revelation caused uproar in India. Viceroy Lord Linlithgow was furious, while Deputy Commissioner Janvrin speculated that Bose sought foreign aid. Bose himself termed it "mahabhinishkraman"—a great departure—to assess the war and contribute to the fight. Bose's escape from his Elgin Road house exemplifies audacious leadership. It shifted the independence struggle's paradigm, inspiring future generations. Though his alliances during WWII remain controversial, the ingenuity of slipping past 62 agents, traversing 200 miles on foot, and navigating international diplomacy underscores his commitment. This journey, fraught with peril, transformed Bose from a confined leader to Netaji, a global symbol of resistance.

Bibliography

Chandrachur Ghose, Bose: The Untold Story Of An Inconvenient Nationalist, pp.376-454.

The Last Pagan Emperor: Julian the Apostate’s defence of Old Gods

Rome in 320 AD was an empire in the middle of a identity crisis. From the misty forests of Britain to the mountains of Armenia, the Roman world was shifting. For centuries, the "Old Gods": Jupiter, Mars, and Apollo were the heartbeat of the state. But a new movement called Christianity was sweeping through the cities, and after Emperor Constantine converted, the ancient altars began to go cold.

The old world was fading. But one Roman emperor tried to get back Rome to its old gods. His name is Flavius Claudius Julianus. History remembers him as the Julian the Apostate.

A Childhood Forged in Blood

Julian wasn’t born a rebel; he was born into a nightmare. After his uncle Constantine the Great died in 337 CE, the imperial family turned on itself. Julian’s cousin, Constantius II, ordered a massacre to wipe out any rivals. Julian was only six years old when he watched his father and eight of his relatives murdered.

He and his brother were only spared because they were too young to be a threat. Julian was sent away to a remote estate, raised under the watchful eye of the very man who killed his family, and forced to live as a devout Christian. He never forgot that "vicious hypocrisy." To the world, he was a quiet Christian boy. In private, he was a soul in revolt.

Julian became an obsessive student. He buried himself in the works of Homer, Plato, and Aristotle. While the Emperor’s spies watched him, he was secretly reading forbidden scrolls on pagan philosophy and magic.

He lived a double life. In the lecture halls of Athens and Ephesus, he pretended to be a pious Christian, but in the shadows, he was meeting with philosophers and occultists. He didn't have many friends; he had books. He even memorized Caesar’s accounts of the Gallic Wars. At the time, it seemed like a harmless hobby for a lonely nerd. Nobody knew those books were teaching Julian how to lead an army.

The Accidental General: Julian the Caesar

In 355 CE, the empire was falling apart on its borders. Constantius II needed a family member to lead the troops in Gaul, and Julian was the only one left alive. The Emperor sent him to the front lines, likely hoping the Germanic tribes would kill him so he wouldn't have to do it himself.

But the "bookish" prince surprised everyone. Julian used his study of ancient tactics to crush the barbarian tribes. His soldiers—many of them still pagans—absolutely loved him. When the Emperor tried to strip his power, the troops revolted. They surrounded Julian’s palace in Paris and declared him the new Emperor.

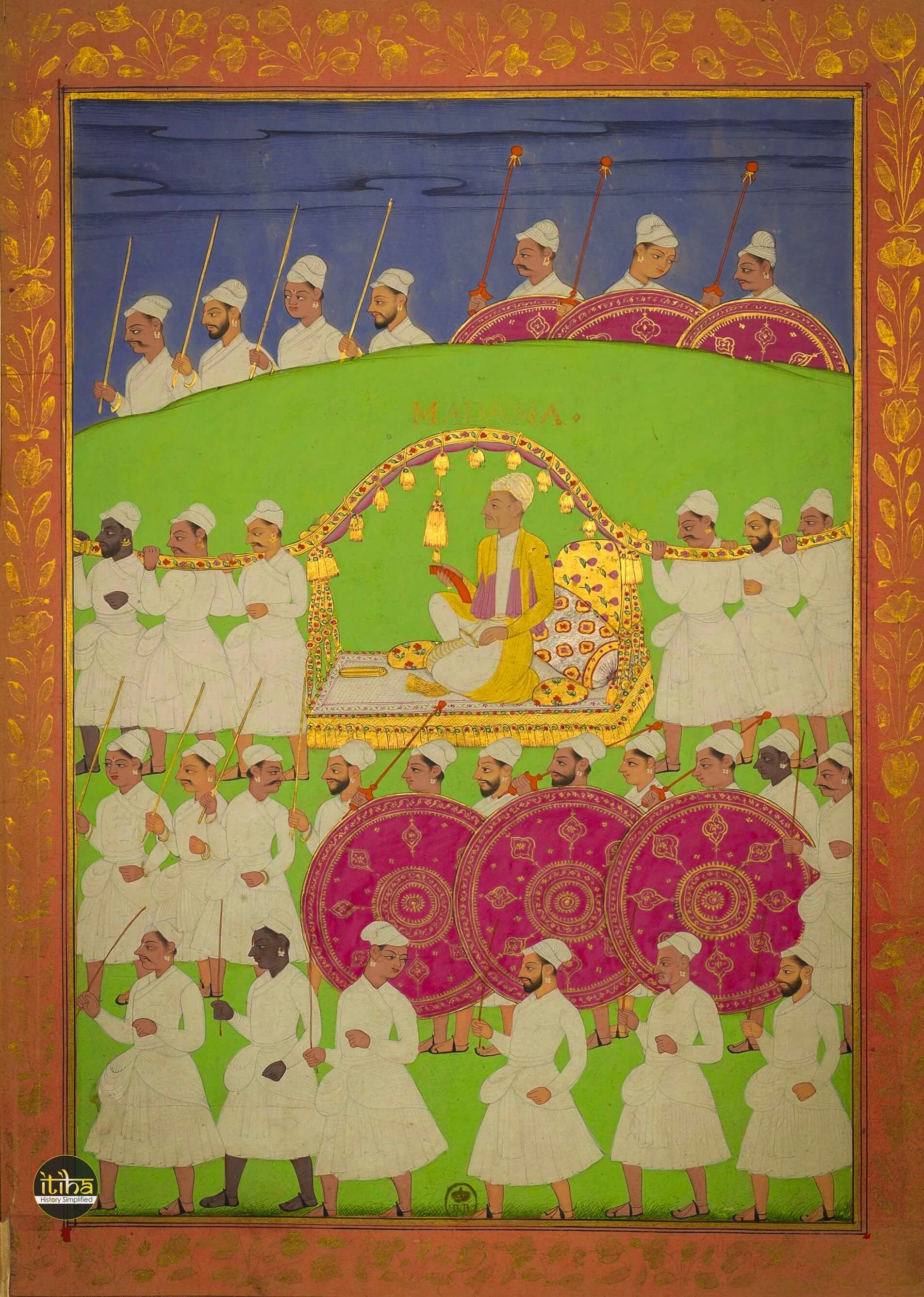

Artistic depiction of Julian

Civil war was coming, but fate stepped in: Constantius died on his way to the battle. In 360 CE, the survivor became the sole ruler of Rome.

The Intellectual War: "Against the Galileans"

Julian didn’t just want to reopen temples; he wanted to win the argument. He wrote a scathing book called Against the Galileans to show why he believed Christianity was a mistake. He used three main "logic bombs" to challenge the Church:

1. The "Local" God of the Hebrews

Julian argued that the God of the Bible wasn't a universal creator. He asked: if this God is the father of all people, why did he ignore the rest of the world for thousands of years? Why would a "universal" God restrict his laws to a tiny tribe in Palestine while leaving the rest of the human race to live in ignorance? To Julian, this proved the Jewish God was just one of many "national" gods, not the king of the universe.

2. A Lack of Achievement

He looked at history and asked a simple question: What has this tradition actually built? He pointed out that the pagan gods had granted Rome world-changing power and wisdom for two millennia. Meanwhile, the Hebrews had often lived as slaves or subjects. He mocked Christians for relying on "childish" stories while ignoring the courage and philosophy of the Greeks—wisdom that Christians ironically claimed was inspired by the devil.

3. The Great Hypocrisy

Julian’s sharpest critique was that Christians were "apostates" from everywhere. He argued they had abandoned the beauty of Greek culture, but they also refused to follow the actual laws of the Jews—like sacrifice and circumcision. He pointed to the Bible to show that Moses intended his laws to be eternal. He accused the Apostle Paul of "inventing" a new religion just to win converts, calling the whole movement "an insult to reason."

Julian's most famous move was a ban on Christian teachers. He forbade them from teaching the Greek classics. His logic was cutting: "If you don't believe in our gods, why are you teaching our books? If you think these authors are wrong about the divine, go back to your churches and teach Matthew and Luke."

“Did the pagan authors not receive all their learning from the gods? I think it absurd that Christians who explain the works of these writers should dishonour the gods whom the pagan authors honoured. If Christians feel that the pagan authors have gone astray concerning the gods, then let them go to their churches, and teach only Matthew and Luke”

By controlling the schools, he intended to ensure the next generation of elite Roman children would be raised as pagans. He used the term "Galilean" specifically to make the faith sound like a backwater, uncultured superstition from a provincial village.

The Failure of the "Pagan Church"

Julian had a strange problem: the Christians were better at being kind. He complained that the "impious Galileans" looked after not only their own poor but the pagan poor as well.

“ Baptism does not take away the spots of leprosy, nor the gout, nor the dysentery, nor any defect of the body… and also adultery, rapine, and all the crimes of the soul”

So, Julian tried to turn paganism into a "church." He told pagan priests they had to stop going to taverns and start acting morally. He told them they had to start giving to the poor. But the pagans didn't want a "Pagan Pope" telling them how to live. When he visited the famous Temple of Apollo at Daphne, expecting a crowd, he found only one old priest with a single goose to sacrifice. The fire was going out, and Julian was the only one left trying to fan the flames.

The Final Skirmish in Persia

In 363 CE, Julian led 80,000 men into the heart of Persia, hoping a massive victory would prove the old gods were still powerful. It was a disaster. He was lured too deep into enemy territory, and his supply lines were cut.

During a messy retreat, Julian heard a skirmish and rushed out to lead his men—forgetting to put on his armor. A spear caught him in the liver. That night, at just 32 years old, Julian died in his tent while debating philosophy with his friends.

The legend says his last words were, "Thou hast conquered, Galilean." Whether he said it or not, the sentiment was true. With his death, the last pagan light in the Roman Empire went out. His successor was a Christian, the temples were closed for good, and the world moved on.

But for two years, because of one man’s childhood resentment and a love for old books, the history of the world almost went in a completely different direction.

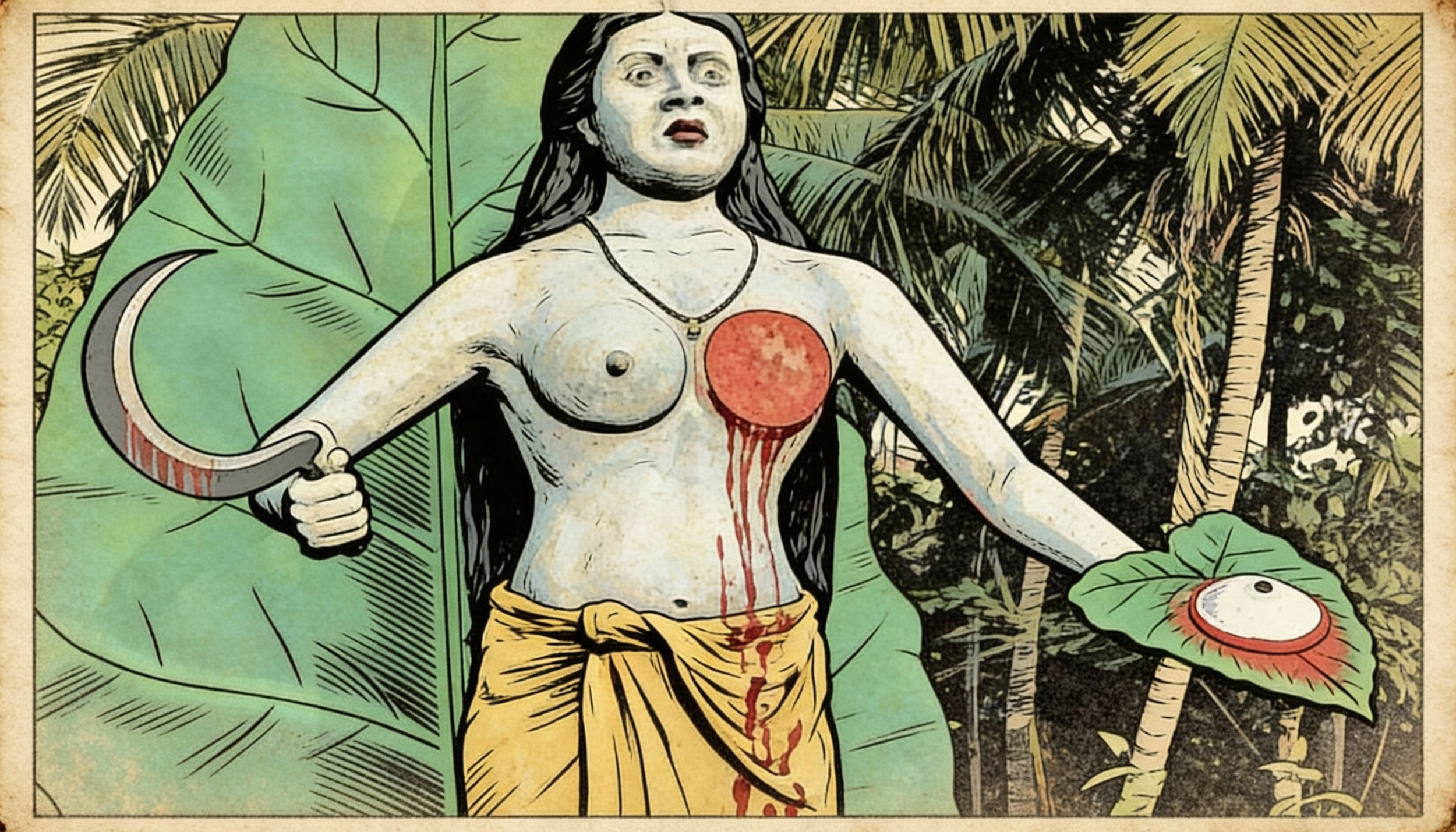

The True History of Mulakkaram

Artistic depiction of the story of Nangeli, an Ezhava woman to have lived in the early 19th century in Cherthala in the erstwhile princely state of Travancore in India, and supposedly cut off her breasts in an effort to protest against a tax on breast.

A commonly cited misconception associated with caste-based discrimination in Kerala is the so-called “Breast Tax” Central to this narrative is the legend of Nangeli, described as a lower-caste woman from nineteenth-century Travancore (present-day Kerala) who allegedly protested the imposition of this tax by severing her breasts and presenting them to a tax collector, an act that purportedly resulted in her death from blood loss. This story was even repeated by the ex-CJI DY Chandrachud. Although this story has gained prominence as a symbol of resistance against caste and gender oppression, several historians argue that the story lacks contemporaneous documentation and is rooted primarily in later folklore. Notably, early records do not even identify Nangeli by name, raising serious questions regarding the historical authenticity of the narrative.

The term “Breast Tax” commonly referred to as Mulakkaram, is used to describe a historical practice in the princely state of Travancore that is often interpreted as reflecting the intersection of caste and gender hierarchies. This tax is frequently portrayed as being imposed on women from lower-caste communities such as the Nadar and Ezhava, and is cited as an instrument of social subjugation during the nineteenth century. However, while certain taxation practices undoubtedly reinforced social stratification, the precise nature, scope, and intent of Mulakkaram remain subjects of scholarly debate. The lack of clear legal documentation suggests that some modern interpretations may rely more on retrospective moral frameworks than on verifiable historical evidence.

Historically, numerous taxation systems that appear unjust or irrational by contemporary standards were normalized within their original socio-cultural contexts. These fiscal measures reflected the economic priorities, political structures, and social norms of their respective periods. Over time, as ethical standards and societal values evolved, many such taxes were rendered obsolete or indefensible. For example, eighteenth-century England imposed a tax on wig powder, a commodity associated with aristocratic status and luxury. Given the material similarity between wig powder and other aromatic powders, this tax effectively extended to a wide range of cosmetic products. Comparable levies included the window tax, calculated based on the number of windows in a building; the candle tax, imposed on wax candle usage; and the soap tax, which targeted a basic household necessity. Although these measures generated revenue, they disproportionately affected certain social classes and were eventually abolished due to growing public opposition.

A similar pattern can be observed in the case of the Chinese Head Tax in Canada, enforced until 1923. This racially discriminatory policy targeted immigrants of Chinese origin and was explicitly designed to restrict Chinese migration while extracting economic benefit from an already marginalized community. Rooted in the xenophobic attitudes of the time, such a tax would be considered a blatant violation of equality and human rights if proposed in contemporary society. Its eventual repudiation illustrates the transformation of societal norms regarding race, justice, and citizenship.

These examples demonstrate how taxation policies, once consistent with prevailing ideologies, can later be recognized as manifestations of structural injustice. They underscore the necessity for fiscal systems to evolve in accordance with ethical progress and social equity. In this broader context, Kerala too witnessed several forms of taxation that appear unusual by modern standards but were widely accepted at the time of their implementation.

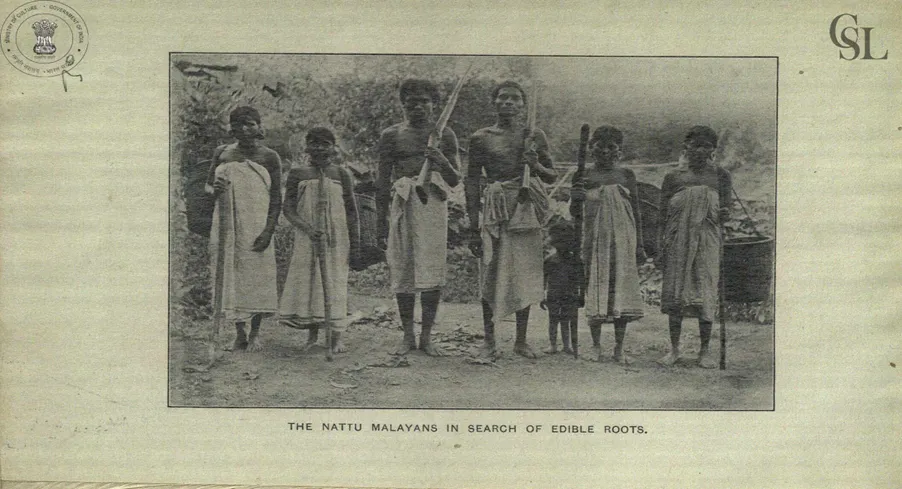

These included taxes such as Mulakkaram (breast tax), Meesakkaram (moustache tax), ladder tax, death tax, and taxes on roofing materials. Importantly, many of these were not formal statutory taxes enacted through royal decrees or codified laws. Instead, they often emerged from customary practices that gradually acquired the character of obligatory payments. Both men and women engaged in agricultural and domestic labor were required to pay various fees for rights related to land cultivation (Verumpattam) and residence (Koodiyedappu). Gender distinctions in these payments were symbolically indicated through references to physical markers such as breasts for women and moustaches for men, rather than constituting literal taxes on the body.

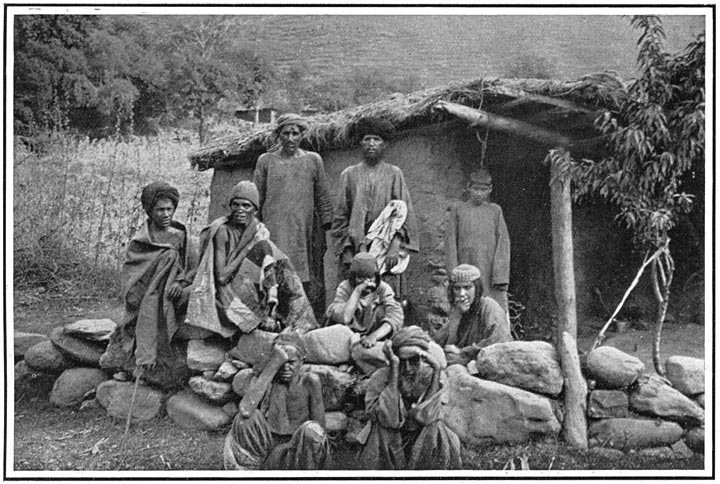

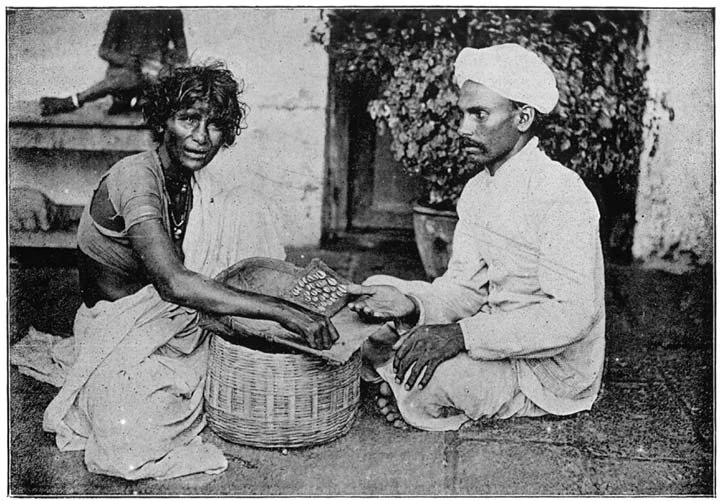

A persistent contemporary myth claims that lower-caste communities were systematically forced into nudity by upper castes through prohibitions on upper garments and punitive taxation. Historical evidence, however, complicates this assertion. Ethnographic works such as The Cochin Tribes and Castes (1909) document visual representations of both upper- and lower-caste women who appeared unclothed above the waist. These depictions suggest that upper-body nudity was influenced by regional customs, climatic conditions, and social norms rather than being solely the result of caste-based coercion.

This is an image of a tribe community called “Kadar,” where the women are covering the top part of their bodies.[1]

An image of a tribe community called “Nattu Malayan,” the women are covering the top part of their bodies.[2].

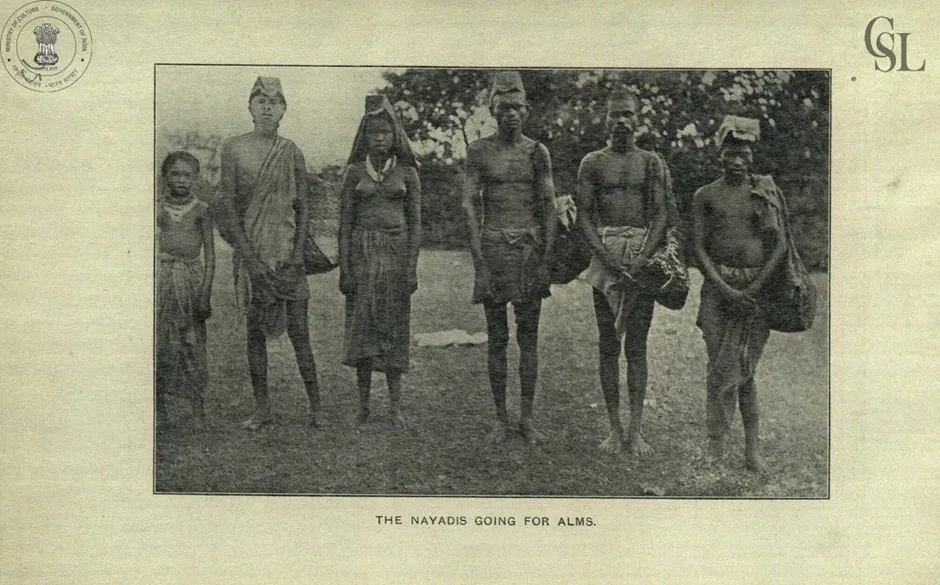

An image of a tribal community called “Nayadis” shows that the women are not covering the top part of their bodies.[3]

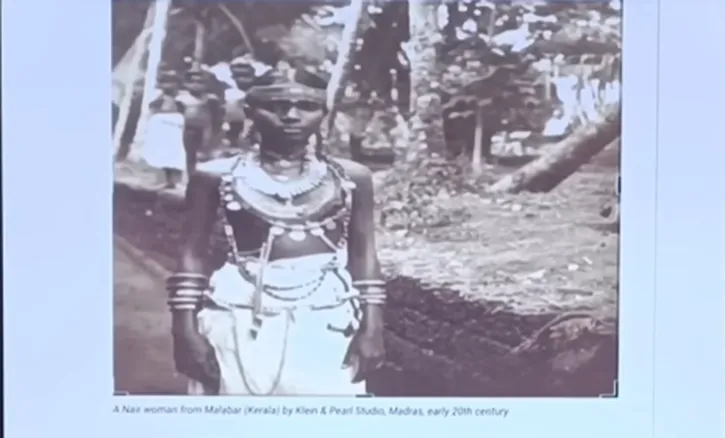

An image of a girl from the community called “Nair/Nayar,” the woman is not covering the top part of their body.[4]

Another image of a girl from the “Nair/Nayar”, community the woman is not covering the top part of their body.[5]

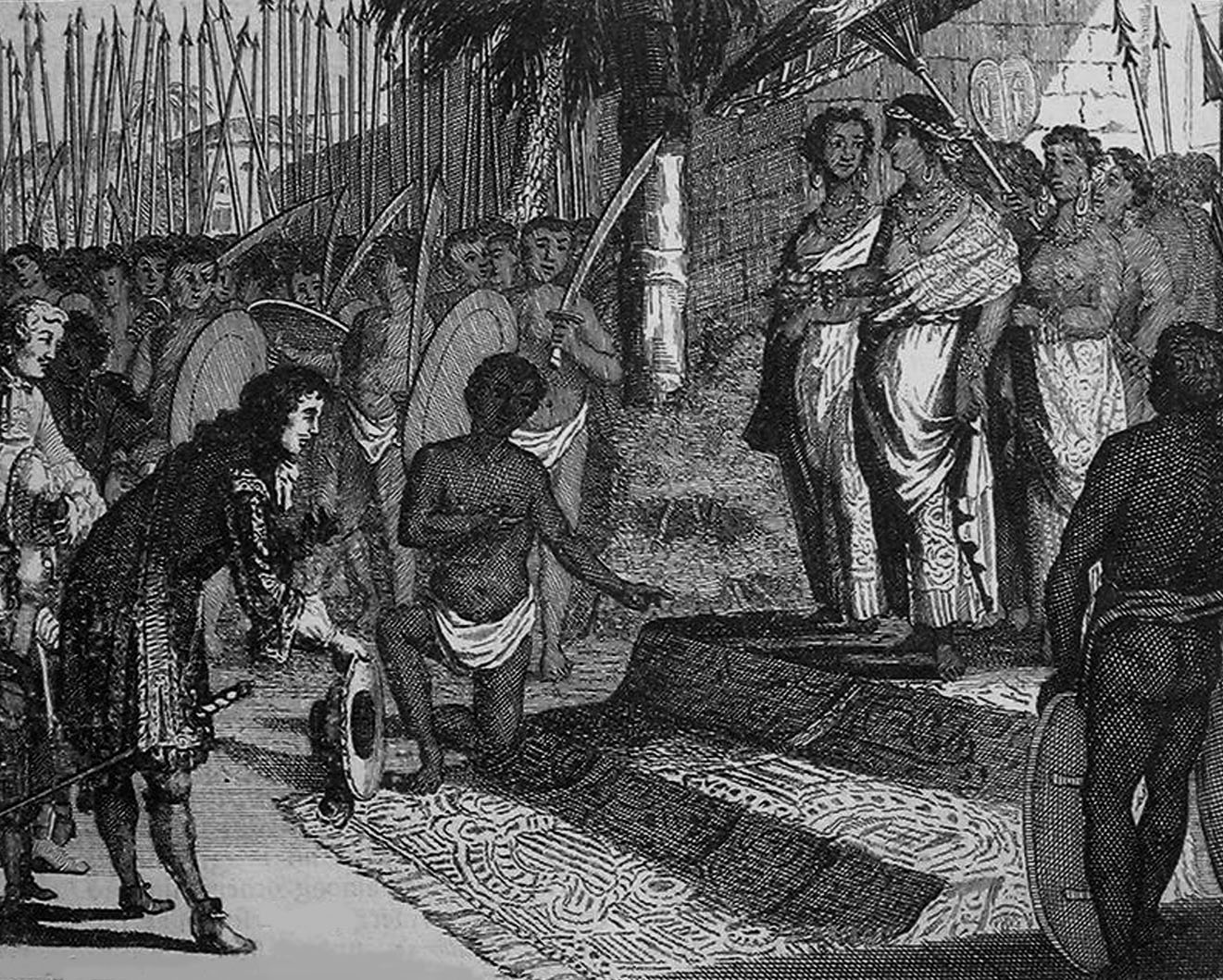

The traveler Johannes Nieuhof records in his work Voyages and Travels into Brazil and the East-Indies that:

“The 2nd of March with break of day,

The author goes to the queen of Koulang.The viceroy of the king of Travancore, called by them Gorepe, the chief commander of the Negroes, called Mattia del Pule, and myself, set out for the court of the queen of Koulang, which was then kept at Calliere. We arrived there about two o’clock in the afternoon, and as soon as notice was given of our arrival, we were sent for to court, where, after I had delivered the presents, and laid the money down for pepper, I was introduced into her majesty’s presence. She had a guard of above 700 soldiers about her, all clad after the Malabar fashion, the queen’s attire being no more than a piece of calico wrapped round her middle, the upper part of her body appearing for the most part naked, with a piece of calico hanging carelessly round her shoulders. Her ears, which were very long, her neck and arms were adorned with precious stones, gold rings and bracelets, and her head, covered with a piece of white calico. She was past her middle age, of a brown complexion, with black hair tied in a knot behind, but of a majestic mein, she being a princess who showed a great deal of good conduct in the management of her affairs. After I had paid the usual compliments, I showed her the proposition I was to make her in writing, which she ordered to be read twice, the better to understand the meaning of it, which being done, she asked, whether this treaty comprehended all the rest? and whether they were annulled by it? Unto which I having given her a sufficient answer, she agreed to all our propositions, which were accordingly signed immediately.”[6]

Several cinematic representations have portrayed the narrative of Nangeli and the so-called Breast Tax through a lens of heightened emotional appeal. These portrayals often rely on dramatization rather than verifiable historical evidence, thereby reinforcing a contested and largely unsubstantiated account. Such representations risk shaping public perception through selective storytelling rather than critical historical inquiry.

Several cinematic representations have portrayed the narrative of Nangeli and the so-called Breast Tax through a lens of heightened emotional appeal. These portrayals often rely on dramatization rather than verifiable historical evidence, thereby reinforcing a contested and largely unsubstantiated account. Such representations risk shaping public perception through selective storytelling rather than critical historical inquiry.

In parallel, this narrative has been appropriated by certain evangelical groups, who have employed it as part of broader conversion-oriented discourses aimed at marginalized communities, including sections of the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe populations. Scholars have noted that the use of emotionally charged historical narratives in this manner can obscure historical complexities and instrumentalize suffering for ideological purposes.

Additionally, some commentators have attributed the abolition of the alleged Breast Tax to Tipu Sultan, despite the absence of credible historical evidence supporting such claims. These assertions often conflate distinct historical contexts and timelines, resulting in anachronistic interpretations. Furthermore, references to the Breast Tax have, in certain cases, been invoked to rationalize or contextualize episodes of communal violence, including the persecution of Mandyam Iyengar communities.[7] The use of disputed historical narratives to justify or explain acts of violence raises serious ethical and historiographical concerns, underscoring the importance of rigorous, source-based analysis.

Citations

[1] The Cochin Tribes and Castes, Vol 1, p.25.

[2] Ibid., p.35.

[3] Ibid., p.52.

[4] A Nair woman from Malabar (Kerala) by Klein & Peail Studio, Madras, early 20th century.

[5] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Breast_exposed_Nayar_Girl.jpg

[6] Johannes Nieuhof, Voyages and Travels into Brasil and the East-Indies, p.218-19.

[7] Vikram Sampath, Tipu Sultan: The Saga of Mysore’s Interregnum (1760–1799),pp.288–289.

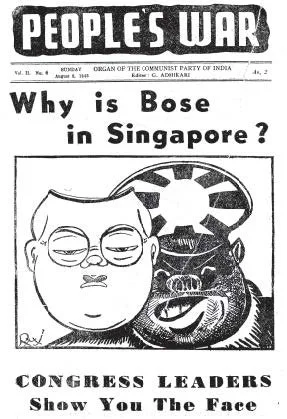

The British, The Congress, and The RSS

Is RSS a fascist organization? This is what the British RAj called them Congress after independence continued to call them as a fascist organization. What are the facts?

Time and again, Congress leaders spew baseless rhetoric about the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Recently, Priyank Kharge, a “Dalit” leader, three-time MLA from Chittapur, and full-time RSS-obsessed heckler and a part-time politician, never misses a chance to take cheap shots. In a recent ‘X’ post, he tried to mock the RSS with a series of hollow questions, including the tired claim that the RSS never took part in the freedom struggle.

Naturally, he didn’t bother to provide a shred of evidence. Expecting factual references from Congress’s noise-makers is like expecting logic from chaos; it’s simply not going to happen. Just like that, we repeatedly see Congress members shamelessly peddling absurd and historically illiterate comparisons between the RSS and the Nazis. This is not just a lazy slur; it is a deliberate distortion rooted in a calculated political history that deserves to be exposed. Let's start with the founder of RSS himself. Dr. Hedgewar. In 1905, as the flames of the Swadeshi movement swept across India, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Antaji Damodar Kale founded the ‘Paisa Fund Society’ to strengthen the nationalist cause. A young, fiercely patriotic K. B. Hedgewar threw himself into the effort, going door-to-door to collect funds for the mission. Not stopping there, he joined the Arya Bandhav Veethika, an organisation formed by Nagpur’s revolutionaries to spread the spirit of Swadeshi, and began visiting schools, igniting in students the resolve to reject foreign goods and embrace indigenous pride.[1]

At just sixteen, Hedgewar rallied together a circle of sharp, restless students, forging a discussion group that debated the issues of the day. His growing nationalist fire soon drew him into the covert network of the Deshbandhu Samaj, an underground collective quietly shaping the revolutionary undercurrent of the era.[2] Hedgewar’s patriotism went further in September 1907, when he and several fellow students defiantly raised the slogan Vande Mataram during a school inspector’s visit. Ordered to apologize, Hedgewar refused outright, choosing principle over punishment. His unyielding stance led to his expulsion, and it was widely believed that he was the chief force behind the students' coordinated act of resistance.[3]

According to his childhood friend Balwant Mandelkar, Hedgewar, along with a small circle of determined students in Nagpur, had secretly learned bomb-making techniques in a clandestine workshop reportedly organized by B. S. Moonje between 1905 and 1906.[4] The following year, in August, Hedgewar threw a homemade bomb at a local police station. The attempt failed to hit its mark, and with no evidence left behind, he slipped through the grasp of colonial authorities. Yet his revolutionary spirit didn’t go unnoticed for long. He was soon arrested for delivering a fiery political speech demanding an end to British rule before a massive crowd gathered for the Dussehra burning of Ravana’s effigy. Thanks to the intervention of influential local leaders, he was released, and the charges were withdrawn. These events pushed Hedgewar deeper into nationalist circles.

N.H. Palkar, the author of ‘Man of the Millennia-Dr. Hedgewar’ notes that it was Guha who first ushered Hedgewar into the inner circle of the Anushilan Samiti, giving him access to one of Bengal’s most influential revolutionary networks.[5] Hedgewar is also believed to have formed a close association with Shyam Sundar Chakravarti, a hardened nationalist and vocal critic of Chittaranjan Das. Some accounts further claim that he maintained contact with towering figures such as Motilal Ghose, Rash Behari Bose, Ashutosh Mukherjee, and Bipin Chandra Pal. However, these assertions remain unproven and lack documentary evidence.[6]

Ramlal Bajpayee, a lawyer residing in Calcutta during this period, records in his autobiography that Hedgewar’s true purpose in going to Calcutta was far deeper than formal studies; he sought to master the workings of clandestine revolutionary societies and forge a living bridge between the nationalist movements of Maharashtra and Bengal. Driven by this mission, Hedgewar shuttled between Nagpur and Calcutta repeatedly from 1910 to 1913, cultivating networks, absorbing underground methods, and weaving together the revolutionary currents of both regions.[7]

Anushilan Samiti flag

Bhupati Majumdar, a young Anushilan Samiti member who would later serve as a minister in the West Bengal government, recalled in his memoirs the encounters he had with Hedgewar during those turbulent years. Majumdar states that Hedgewar, acting as the key liaison for Maharashtrian revolutionaries operating in Bengal, maintained direct contact with Jatindranath Mukherjee, the legendary ‘Bagha Jatin.’ He further claims that Hedgewar actively supported Jatin’s covert efforts to procure arms and ammunition from abroad, a daring enterprise that would later be known as the Hindu–German conspiracy.[8]

Whatever the precise extent of Hedgewar’s involvement with Bengal’s revolutionary networks, one fact was undeniable: the Calcutta police had already marked him as an ‘extremist student’. His movements did not go unnoticed. By early 1912, he had drawn the attention of the Director of Criminal Intelligence, and colonial surveillance tightened around him, reflecting the growing unease British authorities felt toward young nationalists who refused to stay within their control. Calcutta, reported:

On January 31st, Narayan Damodar Savarkar arrived at the Maratha Lodge in Prem Chand Boral's Street and took up his residence there. It is said that Dr. S.K. Mullik is not prepared to admit him as a student of the National Medical College. Soon after his arrival Savarkar was introduced to Hidgewar (sic), Ane, and Naik, three well-known extremist students of the Santi Niketan Maratha Lodge.

On February 3rd, D.V. Vidhwans, the son-in-law of B.G. Tilak, arrived at the Maratha Lodge in Prem Chand Boral's Street from Poona on his way to see Tilak in Mandalay. On his arrival the student Hidgewar mentioned above went and fetched Babu Shyam Sundar Chakravarti (one of the deportees) to the Lodge, and all three had a long conversation. Shyam Sundar Chakravarti is again coming to the front as an extremist.[9]

Hedgewar travelled tirelessly across the Hindi-speaking regions of central India, widening the reach of the weekly and, in the process, forging relationships that would later prove indispensable when he founded the Sangh.[10] His growing disillusionment with the Congress’s definition of Swaraj, as nothing more than self-government within the British Empire, pushed him to chart his own path. He established the Nagpur National Union, an organisation committed to the goal of complete independence.[11]

Portrait of Keshav Baliram Hedgewar (1 April 1889 – 21 June 1940)

Yet this ideological divergence did not prevent him from plunging deeper into the Congress’s organisational activities. These experiences only sharpened his belief in the necessity of a permanent, disciplined cadre. Observing how, in his words, ‘Congressmen are good orators who impress people in the first meeting, but their impact fades from public memory within two or three days,’[12] Hedgewar became ever more convinced that India needed a force rooted in long-term organisation rather than fleeting rhetoric. Hedgewar went ahead and joined the non-cooperation movement in 1920 and addressed several meetings in the party as well as in Bombay.[13]

In 1922, Hedgewar, with the support of Ganga Prasad Pande, set up a National Wrestling School, an institution meant to instill discipline, strength, and nationalist spirit in young men. But the venture soon drew the unwelcome gaze of the Punjab Police and the CID in Nagpur. Their persistent interference and surveillance ultimately forced the school to shut down, yet another reminder of how colonial authorities sought to crush even the smallest sparks of organised national awakening.[14]

To spread the ideals of the Congress and boldly champion the demand for complete independence, Hedgewar, along with a few prominent Congress colleagues, launched a new Marathi daily, Swatantrya, in January 1924. His unwavering sympathy for revolutionary nationalism reverberated through his speeches, writings, and the paper’s editorial line. But his radical stance soon alarmed the more cautious sections of society. Advertisers began to withdraw, and the revenue stream steadily collapsed. Within a year, by January 1925, Swatantrya became financially unsustainable and was forced to shut down.[15]

In 1930, the entire nation was ablaze with the Civil Disobedience Movement. In July, Hedgewar travelled to the small town of Pusad in Yavatmal district to join the satyagraha, temporarily handing over the responsibilities of sarsanghchalak to Dr. L. B. Paranjpe. While in Pusad, he intervened to prevent the slaughter of a cow near the riverbed, an act that sent shockwaves through the town. After addressing a protest gathering there, he moved on to Yavatmal to participate in another act of civil resistance: cutting grass in a government-reserved pasture. Hedgewar was arrested on 21 July along with his fellow satyagrahis and sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.[16] They were housed in makeshift warehouse barracks near the Akola prison, nearly 250 kilometres from Nagpur. As the harsh conditions took a toll on his health, the prison superintendent intervened, and Hedgewar was released on 14 February 1931. It had been over five years since Hedgewar had founded the RSS, and its roots were already spreading. Even during his stay in Pusad, he established a shakha (branch), planting yet another seed of the growing movement.[17] After his release from prison, Hedgewar emerged with renewed resolve. He set out to elevate the RSS from a regional initiative to a truly national organisation, one capable of shaping disciplined, dedicated workers across the length and breadth of the country.

The government of the Central Provinces and Berar had begun watching the RSS with growing unease, scrutinising its every move and debating what punitive measures might be imposed. After the Dussehra celebrations of 1932, official reports voiced explicit concern over Hedgewar’s expanding influence and uncompromising views, signalling that the colonial administration now considered the RSS a force worth monitoring, if not suppressing:

“In the south of the province the most important political feature has been the celebration at Nagpur by the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh of the Dasehra festival, of which advantage is taken each year to hold a ceremonial worship of arms and a review of volunteers. On the present occasion 1,000 uniformed volunteers, under the leadership of Dr. Munje (sic), headed by a band and accompanied by their ambulances, marched past an assemblage which included the Bhonsla Raja G.D. Savarkar, Dr Hidgewar (sic), and others. The drill is reported to have been good. The chief speakers at these celebrations were Dr Munje (sic), and Dr Hidgewar (sic), the second of whom gave an objectionable and provocative address, the main gist of which was that the settlement of the political future of India was for the Hindus alone to decide. No interference either by foreigners or by non-Hindu residents of India should be brooked. The question whether action should be taken against the speaker is under Government's consideration”.[18]

By this time, the government’s continuous surveillance had given it a clearer, though deeply distorted, view of the RSS. Certain sections of the colonial administration began drawing reckless parallels between the organisation and European extremist movements, going so far as to label Hedgewar as a ‘Hitler,’ a comparison rooted more in British fear than fact.

In February 1935, the Criminal Investigation Department’s Special Branch in Allahabad submitted a report to the Chief Secretary of the United Provinces, noting the rapid rise of the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh, described as a volunteer corps parallel to the Congress’ Hindustani Seva Dal. The report detailed the Sangh’s growing network across the Central Provinces, Berar, and the United Provinces, along with its ambition to establish branches throughout the country. It further observed that the Sangh’s presence in the United Provinces was, at that point, concentrated mainly in Benares and strongly centered around disciplined, military-style drills:

The object of this organization is to infuse a military spirit in the Hindus, to impart physical training and to educate them in the use of lathis, spears and daggers and (as was publicly announced at a meeting in Nagpur in 1932) to build up an All-India Hindu Volunteer Corps on the same lines as those of the Nazis under Hitler in Germany. Dr. Hidgewar (sic) (C. P. Who's Who no. 114) is the Hitler of the Sangh.

The All-India Mahasabha held at Delhi in September 1932 passed a resolution admiring the efforts of Dr. Hidgewar for starting this organization and appealed to Hindus all over India to open branches of this organization.[19]

Here we see an almost identical line of accusation, but shockingly, it isn't from the British. It comes from Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru wrote in a letter on 21 November 1947:

… [the] RSS is an injurious and dangerous organization and fascist in the strictly technical sense of the word. We have known about it for many years and some of our colleagues have been up against it for a long time. It is bad enough in Maharashtra where it originated. But the combination of RSS and Punjab has produced something worse. I have little doubt that we have to stand up against this … They are very well organised but extraordinarily narrow in their outlook and completely lacking in the appreciation of any basic problem.[20]

According to Gandhi’s private secretary, Pyarelal Nayar, whenever someone pointed out the good work of the RSS such as ‘refugee relief camps, showing discipline, courage, and capacity for hard work’, Gandhi used to respond by drawing the same parallel as the British did. Comparing the RSS with the Nazis. Gandhi used to respond with, ‘But don’t forget, even so had Hitler’s Nazis and the Fascists under Mussolini.’[21]

Because of the RSS’s disciplined social work and nationalist character, the British administration consistently branded the RSS as a ‘communal’ organisation. This colonial label, weaponised to divide Indian society, soon influenced sections of the Congress as well, leading them to repeat the same charge without scrutiny. It raises a striking question: why did the very organisation distrusted by the British Raj also become a target of suspicion for the Congress?

By the time of 1939, the Sangh had come under the surveillance of not just the provincial authorities but also the central government. On 11 July 1939, the Home Department at Simla dispatched a confidential note to the Chief Secretary of the provincial administration, consolidating all intelligence gathered on the RSS. The report stated that the Sangh’s objective was ‘to train Hindu youths to defend Hinduism and the Hindu community, and to inspire Hindus with a spirit of nationalism and self-confidence, to make them a great national force.’ The note summarized the key incidents of the preceding years to highlight the political, philosophical, and organizational characteristics:

The Sangh had been taking interest in the political movements of the country as a result of which the Central Provinces Government in their circular letter No. 2352-2158-IV, dated the 15/16th December 1932, felt it necessary to issue an order advising Government servants of the communal and political nature of this Sangh and, at the same time, forbidding them to become members or to participate in any of the activities of the organization. This roused the indignation of its chief sponsors, who gave vent to their feelings at the "Sankranti" celebrations on 10th January 1933. Dr Hedgewar asserted that the Government had acted on base insinuations made against the Sangh and denied that it was either a political or a communal body. Sir M.V. Joshi who presided, however admitted that it was a communal organization, but endeavoured to justify its existence in the interests of the Hindus, who he said must be able to defend themselves in times of need. He further said that the Sangh was opposed to the idea of non-violence. Dr Moonje went even further by favouring offence rather than defence and advocated a policy of "Strike first".[22]

By July 1939, Hedgewar’s health had deteriorated severely, forcing him to stay in a rented bungalow at Deolali near Nashik. Yet even as illness confined him, the movement he had founded was expanding with astonishing speed. A Special Branch report from this period reveals the scale of the Sangh’s growth: while the Central Provinces alone had nearly 9,000 members, more than 30,000 others had joined across various provinces, with around 350 shakhas operating nationwide. The report noted that the Sangh believed in cultivating physical strength and discipline, but, based on all available information, concluded that it ‘certainly does not seem to be an unlawful association’.[23]

By the time Dr. Hedgewar’s health finally gave way, he had already transformed the RSS from a modest gathering of a few young men in 1925 into a disciplined force of nearly 40,000 members by 1940. His passing on 21 June 1940 marked the close of a foundational era. From that moment onward, the task of leading, shaping, and expanding the Sangh fell to M. S. Golwalkar, the man millions would revere simply as Guruji.

When the Fourth Security Conference convened at Nagpur in March 1943, the British administration placed the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) on its formal agenda, a telling sign of how seriously the colonial state had begun to view the organisation. The minutes of the conference, apart from revealing the government's suspicion, offer a glimpse into how M.S. Golwalkar had managed the Sangh’s rapid expansion in the preceding years. To the government, the RSS had become a “potential danger.” It was catalogued as anti-British, exhibiting a pro-Japanese inclination in the wartime climate, and, in the eyes of the colonial intelligence machinery, its “fascist tendencies are obvious” in both conduct and organisation. Even as its network spread swiftly across provinces, drawing in increasing numbers of Hindu youth, British intelligence still could not fully decipher the deeper forces driving this surge. Yet on one point the government read the Sangh accurately: the RSS was clearly playing a long game. Golwalkar was steering the organisation away from open confrontation with the state, conserving its energies for a larger moment. The conference recorded this with cold precision: “It is felt that the true purpose of its being lies in the future, and that its revelation will be to the accompaniment of disorder.”[24]

The intelligence departments had gathered a considerable volume of information on the Sangh’s long-term intentions, yet they remained unsure how much of it could be trusted. But such ambiguity was hardly unusual, uncertainty is the permanent shadow of intelligence work, and every assessment carries within it a margin of doubt that must be calculated into policy. By 1939, however, one report stood out for its reliability. It stated that the Sangh’s leadership had reached a strategic decision: they would withdraw from overt political activity for the foreseeable future. Any premature plunge into the political arena, they believed, might expose the organisation to repression and threaten its very survival. Instead, the Sangh dedicated itself to a slower, deeper project, the ideological moulding of Hindu youth, training them for a future confrontation, a future struggle for India’s freedom as envisioned through the Sangh’s own ideological lens. The report said:

They had no faith in democracy and believed that freedom could only be won by violence. In 1940, it was reported that at the end of the annual forty day training selected members of the Sangh are as a rule, tried for a period of three years in different capacities and the most reliable of them are unobtrusively introduced into various departments of Government, such as the army, navy, postal, telegraph, railway and administrative services in order that there may be no difficulty in capturing control over the administrative departments in India when the time comes. This rather sensational inside account of the secret programme of the Sangh cannot be accepted literally, but it can be stated without exaggeration that the Sangh has been for some years working out a long-term policy of steady preparation for the attainment of its ultimate objective of Hindu supremacy.[25]

In December 1942, the Deputy Commissioner of Police in Jubbulpore (Jabalpur) reported that V. D. Savarkar’s call for Hindu youth to enlist in the ongoing war was not an act of loyalty to the British, but part of a deliberate long-term strategy. Savarkar viewed military recruitment as a rare opportunity for young Hindus to acquire discipline, training, and combat experience, resources that would later prove essential for a future revolution aimed at securing and safeguarding India’s independence. This objective, the report noted, was not immediate but strategic and time-bound, designed to mature only when circumstances were favourable. The report said:

It has been made sufficiently clear by the Hindu Sabhaites during the course of their usual talks that V.D. Sawarkar does not think that time was ripe for revolution in the country. The Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh organization, in the opinion of these leaders, which is yet to be sufficiently organized for the said purpose is likely to take every precaution to avoid its being brought to the notice of the Government adversely whereby the Government may not be able to declare the organization illegal or check its progress to the detriment of the interests of the Rashtriya Swayam Sewak Sangh. The organization as a whole remained aloof from the present subversive activities indulged in by the Congressmen.[26]