Criminal Tribes of India: Yerukulas

Imagine being born into a community known for trade through mobility, helping remote villages access essential goods like salt and grain. And then, one day, your entire identity is rewritten by the Colonial state: you're no longer a trader, you're now a criminal.

This is the forgotten story of the Yerukulas in the Madras Presidency. Once vital to India's supply chains, they were systematically pushed to the margins by colonial policies and branded under one of the most oppressive laws in British India: the Criminal Tribes Act (CTA)

From Proud Traders to Economic Ruin

Before the British, the Yerukulas were a large community of traders and cattle breeders, vital to the inland economy. The y were know Yerukulas in Telugu regions, Koravars in Tamil regions, and Korachas in Kanada speaking region, as different branches of the community, were the primary means of distributing salt and grain to far-flung areas. Korava women were also skilled in weaving, foraging, fortune tellers and performing as acrobats and singers. Their mobility and trade routes were not only essential for the economy, but they also helped avert famines. Even the British revenue administration in the early 19th century officially recognized their work as "useful and legitimate."

Their fate changed due to a series of deliberate British policies.

The Salt Monopoly of 1805: The East India Company took complete control over salt production, banning private Indian manufacturers. Salt became a luxury, priced at up to 40 times its production cost. This systematically pushed the Koravas out of the salt economy.

The Railway Act of 1856: The British centralized the distribution of goods through railways, making the Koravas' traditional trade routes obsolete and cutting them off from their primary livelihood.

The Great Madras Famine of 1876: This disaster, combined with new Forest Laws that restricted their grazing lands, decimated their cattle herds, which were the backbone of their trade. Their entire economic system collapsed, leaving them destitute.

With their traditional livelihoods destroyed, the colonial administration's perception of the Koravas changed from "useful traders" to "destitute wanderers" and "threats." They were worried about not being able to extract revenue from these communities. The British needed a new system of control, and they found it in the Criminal Tribes Act.

The Criminal Tribes Act and The Salvation Army's Role

The British first enacted the CTA in 1871, driven by a racist eugenics and classist bias that viewed crime as hereditary. To justify their actions, they used the Yerukulas' own folklore against them, claiming a story about a God Subrahmanya gifting them a house-breaking tool was proof of their innate criminality.

By the 1900s, British authorities were desperate to make these mobile communities conform. In 1911, they amended the CTA to target entire communities, not individuals. Once a tribe was "notified," every man, woman, and child was registered, fingerprinted, and watched.

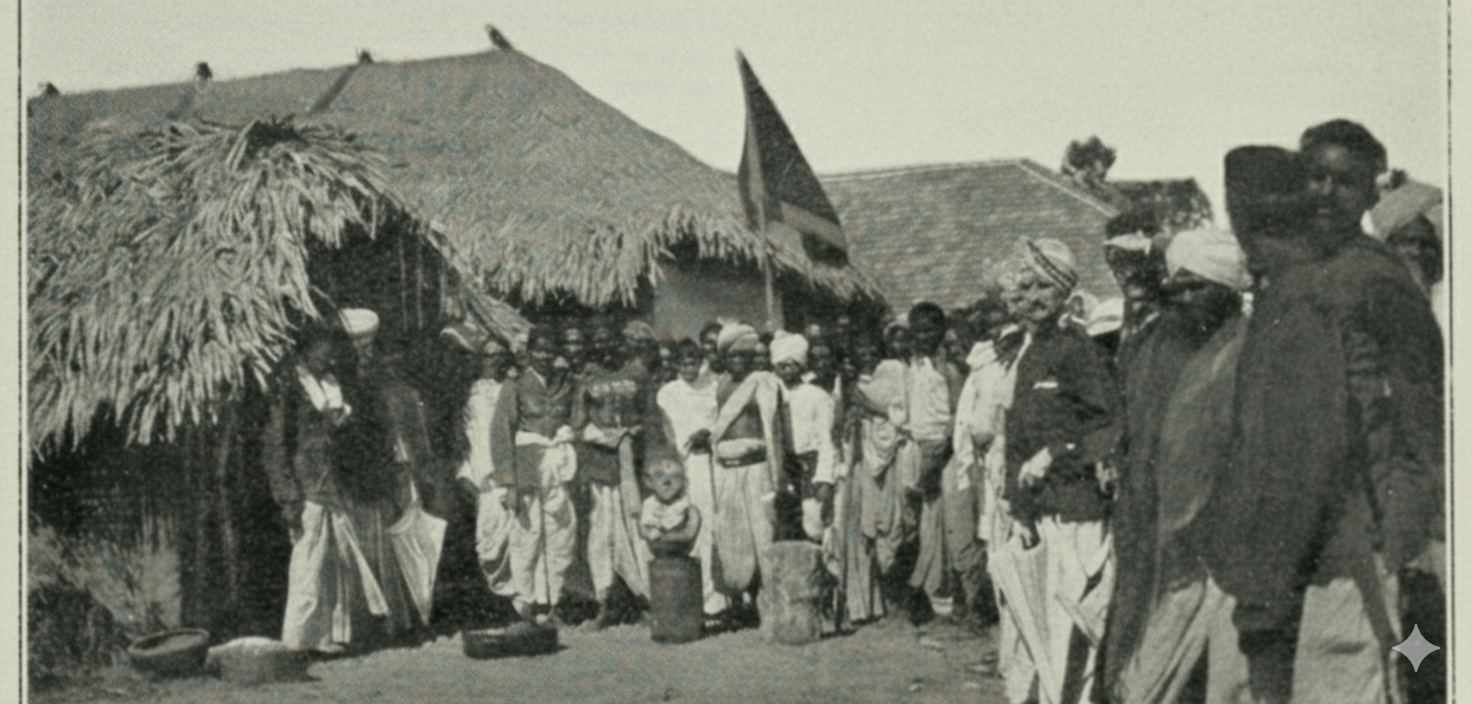

One organization, the Christian missionary group known as the Salvation Army, played a pivotal role in this. The Salvation Army, active in India since 1882, adopted a militaristic approach, with marches, uniforms, and a newspaper called The War Cry. They saw their work as an "imperial campaign." In 1913, with official British backing, they were entrusted with managing settlements for these "criminal populations." In fact, Salvation Army played a big role in influencing CTA

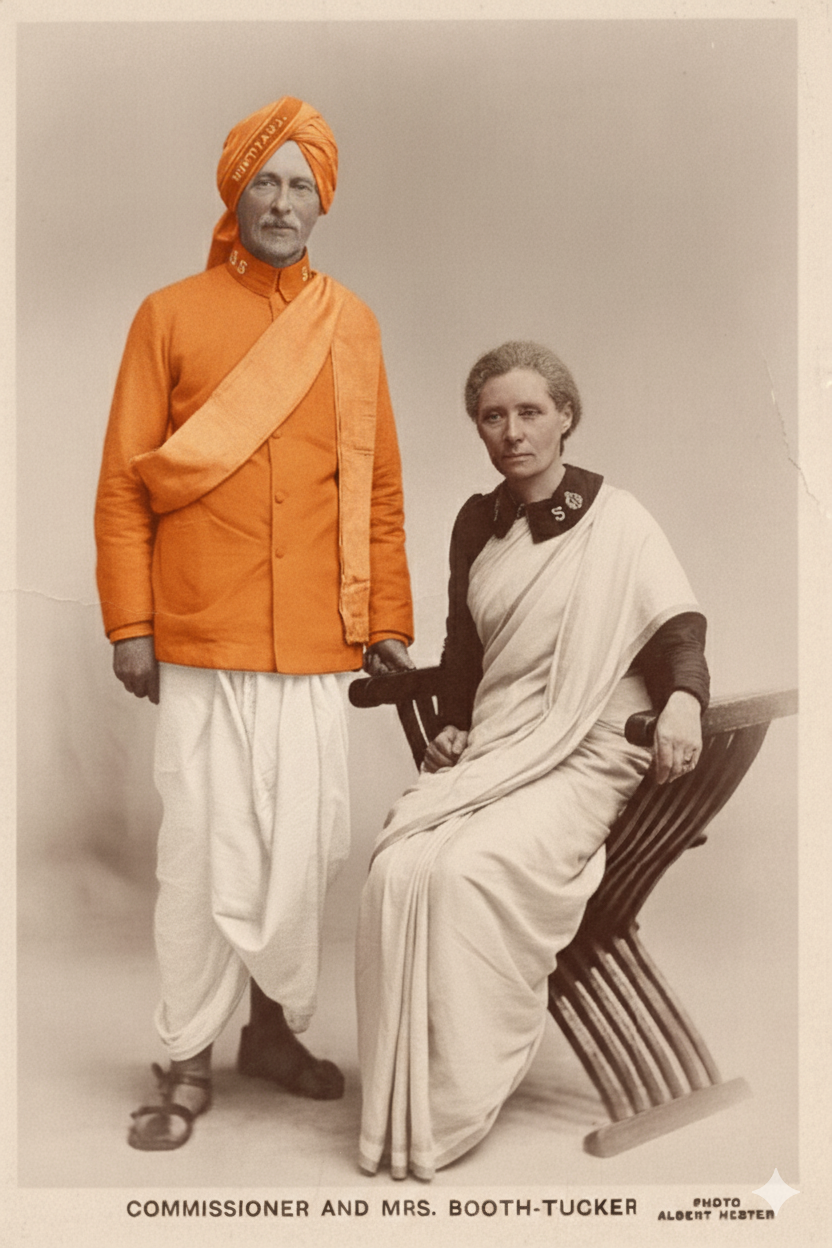

Mr & Mrs Booth-Tucker

Frederick Booth-Tucker, known as "Fakir Singh" in India, was a high-ranking officer of the Salvation Army who modeled his reform strategies on the United States’ assimilation policies toward Native American tribes. Donning saffron robes and presenting himself as a Hindu ascetic, Booth-Tucker employed cultural mimicry to make Christianity appear more familiar to Indian communities.

As Commissioner, he championed the creation of missionary-run settlements that forcibly separated families, placing children in boarding schools and systematically erasing the traditions of India’s so-called “criminal tribes” under the guise of moral rehabilitation. For his service to the British Empire, Booth-Tucker was awarded the prestigious Kaiser-i-Hind Gold Medal (First Class) by Viceroy Lord Hardinge.

Life in the Stuartpuram Settlements: A Concentration Camp

In 1913, the Yerukulas were officially notified and given a stark choice: prison or relocation to a Salvation Army settlement. Many chose the latter, hoping to keep their families together. The most prominent of these settlements was Stuartpuram, promoted as an agricultural colony but, in reality, a concentration camp with back-breaking work and barely enough food to sustain . The settlement was named after Sir Harold Stuart in recognition of his crucial support in acquiring land for the settlement.

Life was brutal. Attendance was taken five times a day, and the Salvation Army served as police, landlord, and employer. Settlers were paid less than local workers and given uncultivable land, which led to the failure of their agricultural "reform."

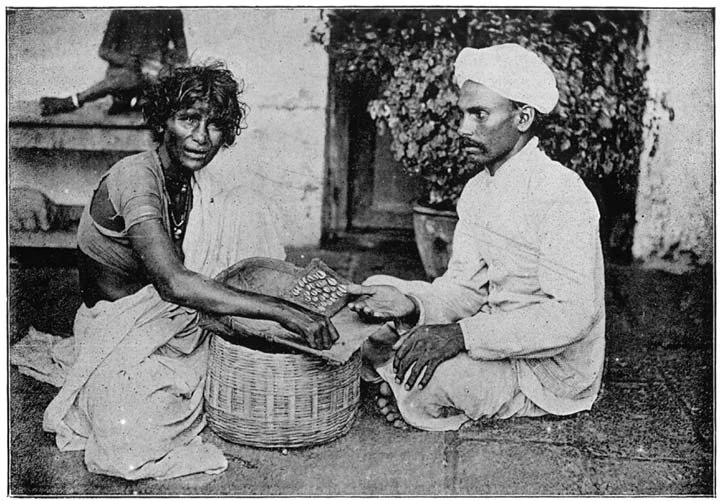

With farming a failure, the Salvation Army strategically pivoted. Under Section 11 of the CTA, they employed the settlers as captive wage labor in nearby British-owned factories, such as the Indian Leaf Tobacco Development (ILTD) Company. The settlers were not "workers" but "offenders under reform," which meant they were not protected by labor laws. Women were the first to be absorbed, enduring grueling 12-to-16-hour days.

Yerakulas were used as strikebreakers

“Free labor was unreliable... but forced labor from our settlers could not escape, absconding was an offense”

Separation of Yerakula Children from Parents

The most devastating aspect of the settlements was the systematic erasure of the Yerukulas' identity. The Salvation Army believed it had to "morally rescue" children from their "criminal parents". Children were separated from their families and placed in boarding schools, where their days were tightly regimented with Christian instruction. This separation severed ties between generations, and oral histories, songs, centuries old folklore and skills were lost forever.

The agony of separation was so intense that some parents took a long-term contract to work on remote tea plantations, a collaboration with the United Planters Association of South India (UPASI). This was a desperate attempt to be reunited with their children, but conditions were horrific, and the infant death rate was staggering. When workers tried to leave, the CTA was used to arrest and return them.

“The settlers objected most strongly of all to The Salvation Army religious services. They complained to Government that we were trying to make them change their religion ! Like most of these tribes they were demonolaters, and their rehgion restricted itself to efforts to appease offended spirits by sacrifices and devil worship of the crudest character.”

The Lingering Stain of History

The CTA was finally repealed in 1949, but India's independent government, burdened by colonial inertia, replaced it with the Habitual Offenders Act. The system was rebranded, not removed. The Salvation Army remained in Stuartpuram, and the narrative of criminality and salvation they had instilled continued.

Today, many descendants still remember the tales taught by the missionaries: "We were criminals. They saved us." But the historical record says something else. In fact, as late as 1946, one member of the Provincial Enquiry Committee remarked that conditions in one of the settlements resembled those of a Nazi concentration camp.

They were never criminals. They were made into one by design.

This is a cautionary tale about how the powerful can rewrite history, criminalize dignity, and erase entire ways of life for profit.

Sources:

Dishonoured by History: "criminal Tribes" and British Colonial Policy by Meena Radhakrishna

Muktifauj : Forty years with the Salvation Army in India and Ceylon

Salvation Army Archives (War Cry)