The Great Escape of Netaji

In the annals of India’s struggle for independence, few episodes are as cinematic and daring as the "Great Escape" of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. While the British Raj believed they had the "rebel" leader securely confined within the walls of his Elgin Road residence in Calcutta, Bose was busy orchestrating a vanishing act that would shift the theater of his revolution from the streets of Bengal to the global stage of World War II.

Based on the historical records preserved by the Netaji Subhas Bose organization and archival accounts, here is the story of that perilous journey. By late 1940, the British government had placed Subhas Chandra Bose under strict house arrest. Following his release from prison on medical grounds after a hunger strike, he was confined to his father’s bedroom at 38/2 Elgin Road. A ring of secret police and intelligence officers surrounded the house 24/7, monitoring every visitor and movement. By that time, Netaji had reached a definitive conclusion that he could not win India's freedom with the Congress/Gandhian ways.

To the outside world, Bose was a broken man, seeking solace in prayer and meditation. He grew a long beard, remained in seclusion, and let it be known that he was considering a life of renunciation as a sadhu. In reality, this was the "bluff of religious seclusion", a psychological smoke screen designed to lower the guards’ vigilance. Certain historical accounts suggest that Savarkar proposed to Netaji the strategy of initiating an armed revolution from abroad.

On 22 June 1940, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose met Savarkar at Savarkar Sadan in Mumbai.

In this meeting, it is said that Savarkar advised Netaji to establish India’s own armed force to fight against the British.

Background: The Road to House Arrest

To understand the escape, we must first contextualize Bose's predicament. Subhas Chandra Bose, born in 1897, was a fiery nationalist whose vision for India's independence diverged sharply from the non-violent path advocated by Mahatma Gandhi. By 1940, Bose had already served as the President of the Indian National Congress twice, but his radical views led to conflicts within the party. He founded the Forward Bloc in 1939, emphasizing armed struggle and socialist principles. The British colonial authorities, wary of his influence, arrested him on December 5, 1940, under the Defense of India Rules. Initially imprisoned, he was transferred to his family residence at 38/2 Elgin Road in Calcutta (now Kolkata) for health reasons, but this was no lenient measure; it was house arrest under strict surveillance. The house, a spacious colonial-era bungalow, became both a prison and a planning ground.

Surrounded by 62 sleuths from the British intelligence, every visitor was monitored, mail intercepted, and movements scrutinized. Bose's health had deteriorated due to a hunger strike in jail, but his mind remained sharp. During his 40 days at home, he immersed himself in spiritual practices, including prayer, meditation, and reading the Bhagavad Gita in his father's bedroom. This period of apparent quiescence masked intense internal deliberations. Bose realized that remaining in India would lead to prolonged imprisonment, stifling his ability to organize resistance. He believed the ongoing World War II presented opportunities to align with Britain's enemies, initially Russia or Japan, to wage an armed struggle from abroad.

Bose's correspondence during this time reveals his frustrations. On December 29, 1940, he wrote to Gandhi, offering cooperation despite their ideological differences. Gandhi's reply was telling: "You are irrepressible whether ill or well. Do get well before going in for fireworks." He added, "With the fundamental differences between you and me, it is not possible till one of us is converted to the other's view, we must sail in different boats, though their destination may appear, but only appear to be the same." This exchange underscored Bose's isolation within the mainstream Congress leadership and solidified his resolve to escape.

The Meticulous Planning Phase

Planning the escape was a clandestine operation involving a network of trusted allies. Bose drew on contacts from the Kirti Kisan Party, including Sardar Niranjan Singh Talib and Comrade Acchar Singh, but arrests disrupted early efforts. The Bengal Volunteers, a revolutionary group, took the lead under Major Satya Gupta and Satya Ranjan Bakshi, who handled logistics and funding. Bose's niece, Ila Bose, played a pivotal role in coordinating within the family.

The escape route was charted via Peshawar to Kabul, Afghanistan, a treacherous path through the North-West Frontier Province, known for its rugged terrain and tribal conflicts. This choice was strategic: Afghanistan was neutral, offering potential gateways to Russia or Europe. To evade detection, Bose would disguise himself as Mohammed Zia-ud-din, an insurance agent from the United Provinces. The plan required precise timing, as a court hearing was scheduled for January 16, 1941. Bose feigned illness to secure a medical extension; his family doctor, Dr. Sunil Bose, refused to issue a certificate, deeming it unethical, but Dr. Mani De stepped in, later facing humiliation from the authorities for his involvement.

Family members were selectively involved to maintain secrecy. Bose's nephews Dwijendra and Aurobindo, along with Ila, assisted in preparations. His brother Sarat Chandra Bose was kept in partial confidence. Crucially, Dr. Sisir Kumar Bose, Sarat's son and a medical student uninvolved in politics, was chosen as the driver due to his efficiency and familiarity with the family's Wanderer car. Sisir had scouted alternative routes to avoid police checkpoints. Bose deceived even his closest kin by pretending to accept impending jail time, ensuring no suspicions arose.

Funds were arranged discreetly, and contingencies were planned for the journey ahead. Mian Akbar Shah, a Forward Bloc leader from the North-West Frontier, visited Bose on December 16, 1940, to finalize the Peshawar-Kabul leg. Shah would meet Bose in Peshawar and arrange escorts. The plan's success hinged on slipping past the surveillance net around the Elgin Road house—a feat that seemed impossible given the 62 agents stationed there.

The Night of the Escape

January 16, 1941, marked Bose's last public appearance at home. As evening fell, the house buzzed with normalcy, but tension simmered beneath. Around 1:30 AM on January 17, Bose, disguised in a long coat, pajamas, and a fez cap as Mohammed Zia-ud-din, bid a quiet farewell to his family. With the help of his nephews, he exited through a side door, evading the watchful eyes outside. Sisir Bose waited in the Wanderer car, engine humming softly.

The drive was nerve-wracking. They headed northwest towards Bararee in Bihar, a distance of about 250 miles, navigating dark roads and potential checkpoints. To maintain the ruse, they posed Zia-ud-din as a traveling insurance agent. Upon reaching Bararee, they rested at the home of Dr. Asoke Nath Bose, another nephew. Here, the deception continued: servants were told Zia-ud-din was a visitor from Calcutta, preventing any leaks.

From Bararee, Sisir drove Bose to Gomoh railway station, where he boarded the Delhi Kalka Mail train under his alias. This leg was critical; any recognition could unravel the plan. Bose arrived at Peshawar Cantonment on January 19, 1941. Mian Akbar Shah met him and escorted him via tonga (horse-drawn carriage) to the Taj Mahal Hotel, then to the home of Abad Khan, a trusted ally.

The escape from the house was a masterstroke of timing and disguise. Back in Calcutta, Bose's absence wasn't immediately noticed. His mother, Prabhavati Devi, feigned ignorance when police inquired, demanding to know what they had done with her son. The British concocted a story of Bose renouncing worldly life, but it was widely disbelieved. Poet Rabindranath Tagore expressed public concern, amplifying the sensation.

The Journey Through India: To the Frontier

With the house escape successful, the real perils began. In Peshawar, Bose faced a language barrier—he couldn't speak Pushtu, the local tongue. To blend in, he adopted the guise of a deaf-mute Pathan, complete with traditional attire. Mian Akbar Shah assigned Bhagat Ram Talwar, a communist and Forward Bloc sympathizer (posing as Rahmat Khan), as his escort. They portrayed Bose as an elderly relative seeking a cure at the Adda Sharif shrine.

On January 19, they left Peshawar by car towards Jamrud, the gateway to the tribal areas. The next day, they detoured to Garhi village on foot, where they were joined by armed Pathan bodyguards for protection. The North-West Frontier was a lawless region, rife with tribal feuds and British patrols. On January 26, 1941—India's Republic Day in modern times—they crossed into tribal territories beyond British control.

The trek covered over 200 miles of rugged terrain, mountains, rivers, and deserts, often on foot, with minimal food and rest. They stayed at the Adda Sharif Dargah, where the Pir provided shelter and rotated bodyguards. Reaching Lalpura by 9 PM one evening, they found refuge with an influential Khan who furnished a Persian letter of introduction: "Rahamat Khan and Ziauddin were residents of Lalpura and were going to the Dargah of Sakhi Saheb." This document proved invaluable when a harassing CID constable in Kabul Serai demanded bribes, taking Bose's gold wristwatch, a family heirloom from his father, Janaki Nath Bose.

Crossing the Kabul River posed another challenge. Without a boat, locals improvised a vessel from inflated leather sacks. The route bypassed Daka to avoid octroi duties, adding to the hardship. Near Thandi, exhaustion overtook Bose; he slept roadside while Rahmat flagged down vehicles. A lumbering lorry laden with goods finally stopped—they clambered atop, enduring freezing winds, snow, and whipping branches. Stops for tea provided a brief respite. At Batghake, they paid duties and bribes, leveraging the Khan's letter, arriving in Kabul Serai by late afternoon on January 31, 1941.

Perils in Kabul: Hiding and Diplomacy

Kabul was a den of intrigue, with spies from various powers. Language barriers compounded issues, Rahmat spoke only Pushtu, not Persian. They initially lodged in a dingy sarai near Lahori Gate, a filthy area teeming with potential informers. Bose's goal was Russian assistance, banking on Soviet sympathy for anti-colonial struggles and the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Efforts to contact the Soviet ambassador faltered; they located the embassy but couldn't gain entry. Days of waiting culminated in stopping the ambassador's car, only to face skepticism.

Dejected, Bose turned to the German minister, Hans Pilger, via Indian bazaar contacts. Pilger, suspecting a British trap (possibly fueled by Communist Party of India agents), involved Berlin and the Italian embassy. Living conditions deteriorated; Bose fell ill in the unsanitary sarai and bribed a suspicious Afghan policeman with Rs 10, then his wristwatch. By mid-February, Rahmat secured shelter with Uttamchand Malhotra, a radio repairman in the Indian neighborhood. A nosy neighbor nearly exposed them, prompting a temporary relocation.

On February 22, 1941, Bose met Italian Ambassador Pietro Quaroni, who described him as "intelligent, able, full of passion, and without doubt the most realistic, the only realist among Indian nationalist leaders." Multiple meetings explored exit strategies. British intelligence intercepted an Italian telegram on February 27, alerting them to Bose's presence. Declassified documents reveal a British order on March 7, 1941, to assassinate Bose via Middle East operatives. Undeterred, Bose wrote articles like "Gandhism in the Light of Hegelian Dialectic" and "A Message to My Countrymen," entrusting them to Rahmat for delivery to Calcutta.

By March 3, Moscow approved a transit visa. On March 10, Bose's photo was inserted into Italian diplomat Orlando Mazzotta's passport. He handed a political thesis and a letter to his brother Sarat to Rahmat. On March 18, 1941, Bose departed Kabul by car with two Germans and one Italian, traversing the Hindu Kush mountains to Samarkand, then by train to Moscow (arriving March 27 or 31, per accounts), and finally by air to Berlin on March 28.

The Frontier's Wild Tribes

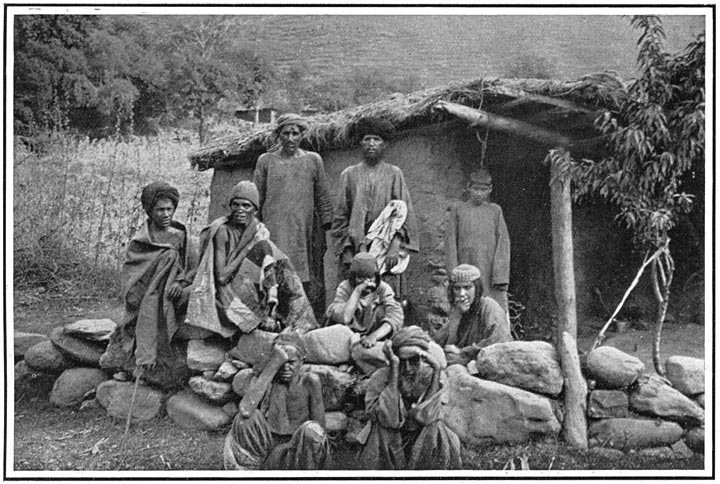

The Afghan frontier, with its Pathan tribesmen and unforgiving landscapes, tested Bose's endurance. This region, depicted in historical accounts as a hotbed of resistance against colonial forces, required navigating tribal loyalties and natural hazards. Bose's adoption of Pathan customs and silence as a "deaf-mute" was a clever adaptation, but the physical toll, cold nights, hunger, and constant vigilance were immense.

Bhagat Ram Talwar, Bose's escort, later emerged as a complex figure, a quintuple spy working for multiple powers. While crucial to the escape, he allegedly betrayed related rebellion plans, leading to arrests and tragedies among Bose's allies.

Arrival in Germany and the Aftermath

In Berlin, Bose was sheltered by the German Foreign Office under Dr. Adam von Trott zu Solz, a non-Nazi who later joined anti-Hitler plots. Bose established the Free India Center, recruited aides, and began broadcasts. He met Joachim von Ribbentrop and Adolf Hitler, pushing for Axis support for Indian independence. The Indian Legion was formed from POWs, and plans for sabotage unfolded. The escape's revelation caused uproar in India. Viceroy Lord Linlithgow was furious, while Deputy Commissioner Janvrin speculated that Bose sought foreign aid. Bose himself termed it "mahabhinishkraman"—a great departure—to assess the war and contribute to the fight. Bose's escape from his Elgin Road house exemplifies audacious leadership. It shifted the independence struggle's paradigm, inspiring future generations. Though his alliances during WWII remain controversial, the ingenuity of slipping past 62 agents, traversing 200 miles on foot, and navigating international diplomacy underscores his commitment. This journey, fraught with peril, transformed Bose from a confined leader to Netaji, a global symbol of resistance.

Bibliography

Chandrachur Ghose, Bose: The Untold Story Of An Inconvenient Nationalist, pp.376-454.